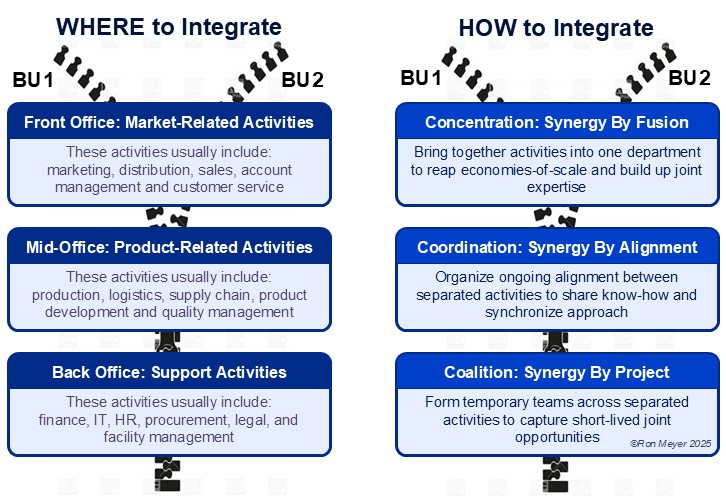

Key Definitions

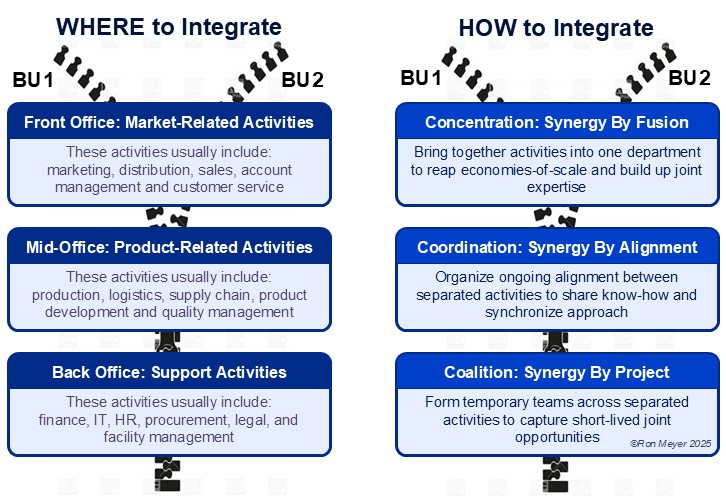

A business unit is a part of an organization that can potentially be run independently, as a separate business. It generally needs to perform front-office activities that are market-facing (such as marketing and sales), mid-office activities that are product-related (such as production and logistics) and back-office activities that are support-oriented (such as HR and finance).

Leaving business units largely independent allows them to be responsive to their specific market demands. But they can also be partially integrated to realize synergies, such as scale economies and market power (see model 64, Corporate Synergy Typology). Therefore, balancing the level of integration is called the paradox of responsiveness and synergy.

Conceptual Model

The Integration Zippers is a model for thinking about various organizational possibilities between the extremes of total separation and full integration of business units. Using the metaphor of a zipper, the model suggests that business units should be integrated starting from “the bottom” up, at each point considering whether further zipping make strategic sense. The left-hand zipper deals with which activities to integrate, proposing that back-office, then mid-office and finally front-office is the preferable order. The right-hand zipper deals with the manner of integration, advising to first consider only using projects, then to weigh whether ongoing alignment would be better, and then ultimately to even contemplate using full fusion.

Key Elements

The two Integration Zippers consist of the following elements:

- WHERE of Integration. Not all activities are as easy to integrate, particularly because integration leads to less responsiveness – less ability to differentiate the activity to fit with the specific demands of the market, and less agility to rapidly adapt to market changes. Generally, the further an activity is from the market, the less responsiveness is required, making a potential synergy more attractive. Therefore, the preferred integration order is:

- First Back-Office. Support activities such as finance, IT, procurement, research, HR, legal and facility management tend to be less business-specific and therefore easier to share across business units, so they should be considered first.

- Then Mid-Office. These are all activities directly contributing to the creation of the product or service, from product development to supply chain, production and delivery, and they can be shared if the creation process is relatively similar.

- Finally Front-Office. These are all activities that directly interact with customers and other market actors, including marketing, distribution, sales, and customer service, and can only be shared if the markets are similar. These should be considered last.

- HOW of Integration. Integration is not a binary choice between “yes” and “no”, but a choice between different levels, from “light” to “tight”, by varying the type of integration mechanism employed – the organizational set-up used to realize the intended synergy. Generally, the tighter the mechanism, the higher the synergy, but also the lower the responsiveness. Therefore, it’s best to start by considering light integration and then evaluate tighter forms:

- First Coalition: Synergy by Project. The lightest integration mechanism is to form temporary teams around specific projects, to allow knowledge to be transferred, best practices to be shared or certain customers to be jointly served, all for a limited time.

- Then Coordination: Synergy by Alignment. If more permanent collaboration is required, a tighter integration mechanism is to formalize ongoing alignment, to ensure that activities on both sides strengthen to each other, while still staying separate.

- Finally Concentration: Synergy by Fusion. If structural coordination is insufficient to achieve the intended synergy, then the tightest integration mechanism will be needed, which is the full fusion of both units’ activities into a merged whole.

Key Insights

- Integration is bringing together business units. When two or more business units give up some of their independence and to work together, this is called integration. Sacrificing their autonomy generally reduces their ability to be responsive to the specific demands of their market but increases synergies. Determining the optimal level of integration depends on finding the preferred balance between responsiveness and synergy.

- Integration has a “where-side” and a “how-side”. Business units need to assess which activities to integrate (the “where” of integration) and in what way to integrate these activities (the “how” of integration).

- Integration can be across three types of activities. “Where to integrate” can be divided into three general categories, based on how far away they are from market demands: Back-office activities (support functions that are often less business-specific), mid-office activities (product-related functions that are more business-specific) and front-office activities (highly business-specific market-facing ones).

- Integration can be at three levels of intensity. “How to integrate” distinguishes three different integration mechanisms: Using coalitions (temporary projects), coordination (continuous alignment) or concentration (permanent fusion).

- Integration should follow the zipper approach. Both “where” and “how” to integrate should be answered by zipping from the bottom up, gradually and thoughtfully considering how far to go to achieve the optimal balance between responsiveness and synergy.

72. Courageous Core Model

Key Definitions

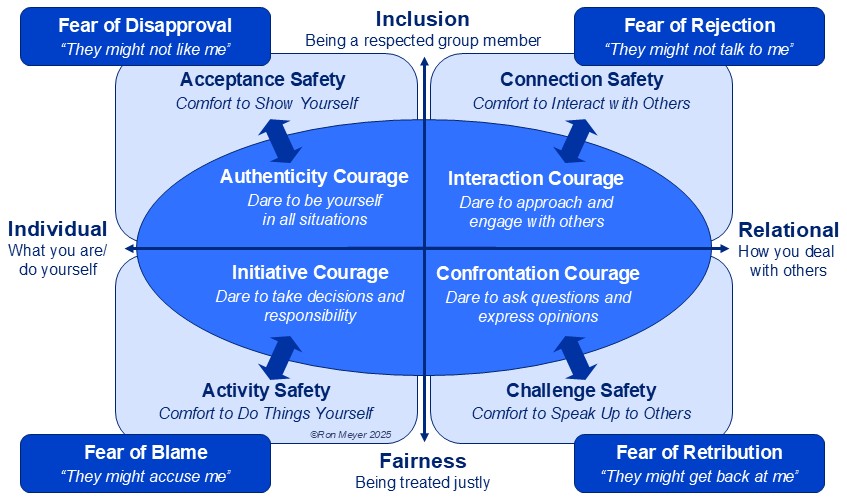

Courage, or bravery, is the quality of overcoming fear – it is the psychological strength to act despite experiencing a feeling of dread. People are courageous when they sense that they face an unsafe situation and still maintain their ability to function.

Soldiers, firefighters and police officers must sometimes deal with a lack of physical safety, but everyone must regularly deal with a lack of psychological safety. People can feel psychologically unsafe if they fear negative social reactions, such as disapproval, rejection, blame and retribution.

Conceptual Model

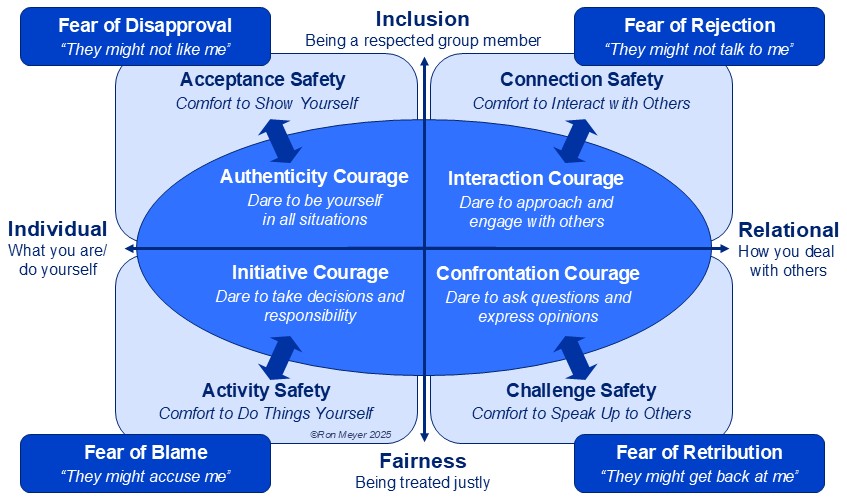

The Courageous Core Model builds on the Psychological Safety Compass (Meyer’s Management Models #40), that outlined four common fears (below in dark blue) and the four related types of psychological safety that leaders should strive to provide to the people around them (in light blue). But while the Psychological Safety Compass highlighted the role of the leader in creating a safe environment, the Courageous Core Model emphasizes the responsibility of every individual to act bravely. The model suggests that no environment can be made entirely safe, so people need to build up a courageous core to dare to function despite their fears. The less safety on offer externally, the more courage that will be required internally.

Key Elements

The four types of courage required are the following:

- Authenticity Courage: Dealing with the Fear of Disapproval. Everyone would like to be accepted for who they truly are, without the need to live up to other people’s expectations. However, in many circumstances, behavioral norms are strict, people are judgmental, and you will be pressured to conform to preconceived notions of how things should be. But instead of caving in to this looming social disapproval, you can exhibit authenticity courage, by staying close to your genuine self. This can include looking and sounding different, coming from a different background, and having different thoughts, opinions and feelings.

- Interaction Courage: Dealing with the Fear of Rejection. Even introverts like it when it is easy to talk to other people and everyone feels at ease in each other’s company. However, in many situations, social interactions are far from smooth, as status differences and group affiliations come into play, giving you a signal that you are not part of the in-crowd. But instead of avoiding people because of the fear of being rejected, you can exhibit interaction courage, by trying to connect, nevertheless. This can range from simply striking up a conversation, all the way to asking to be included in others’ circle or club.

- Initiative Courage: Dealing with the Fear of Blame. To get things done, people need to make decisions and take actions, but there is always a danger that mistakes will be made and/or that things will go wrong. In many situations, the first response to a failure is not to search for a solution, but to seek out the guilty, so taking on responsibilities can be rather risky. In the same way, making tough choices can be dangerous, as dissatisfied stakeholders will vent their anger at the decision-maker. Yet, instead of shying away from taking action, you often need to show initiative courage and risk taking some of the blame.

- Confrontation Courage: Dealing with the Fear of Retribution. It is in the clash of ideas and perspectives that new insights develop, and creative solutions are formulated. So, you would expect that challenging people’s views and asking tough questions would be seen as valuable aspects of group interaction. However, in many circumstances, such diversity of opinion is seen as disruptive and disrespectful, so needs to be suppressed. But instead of faking consensus to avoid the threat of retribution, you can exhibit confrontation courage, by posing uncomfortable questions and suggesting unpopular alternatives.

Key Insights

- Courage is about overcoming fear. Being courageous doesn’t mean you’re not scared, but rather that you have the willpower to act despite being scared. Courage is the quality that makes you choose fight over flight when confronted with a dangerous situation.

- Courage is required when safety is lacking. Without danger, courage is not required. But the more unsafe a situation, the more courage is required to act. Situations can lack physical safety, but more often people need to overcome a lack of psychological safety.

- Courage is about overcoming four types of fear. People can have two types of social inclusion worries, namely the fear of not being accepted for who they are (fear of disapproval) and not being welcomed as social counterpart (fear of rejection). They can also have two types of fairness worries, namely the fear of being unjustly condemned for actions they have taken (fear of blame) and unjustly retaliated against for speaking up (fear of retribution).

- Courage also comes in four types. Fear of disapproval can be countered by daring to be yourself (authenticity courage), fear of rejection by daring to engage with others (interaction courage), fear of blame by daring to take decisions and responsibility (initiative courage) and fear of retribution by daring to express opinions (confrontation courage).

- Courage comes from the inside, safety from the outside. Leaders can try to create a safe environment, but people need to strengthen their inner core of courage themselves. Resilience to danger starts with taking responsibility for building one’s own brave heart.

71. Five Phases of Change

Key Definitions

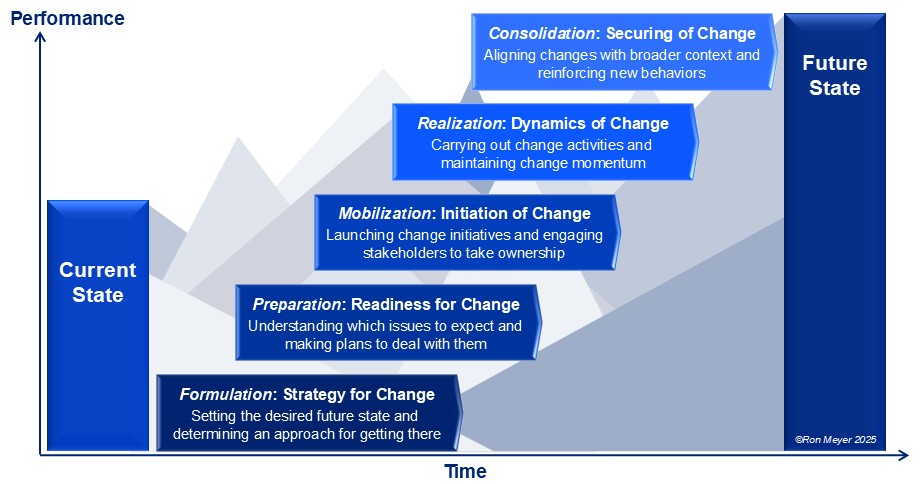

As outlined in the Mind the Gap Model (Meyer’s Management Models #1), organizational change is the process of transitioning an organization (or parts thereof) from a current state to an intended future state. Some organizational changes are incremental (small and gradual), others transformational (large and rapid), while most are somewhere in between.

Few organizational changes take place in a fixed number of orderly steps. Most processes are like rivers – messy streams of activities, occasionally speeding up and slowing down, flowing forward, but also curling back. Therefore, it is better to speak of generic phases or stages in a change journey, instead of thinking in terms of distinct change steps.

Conceptual Model

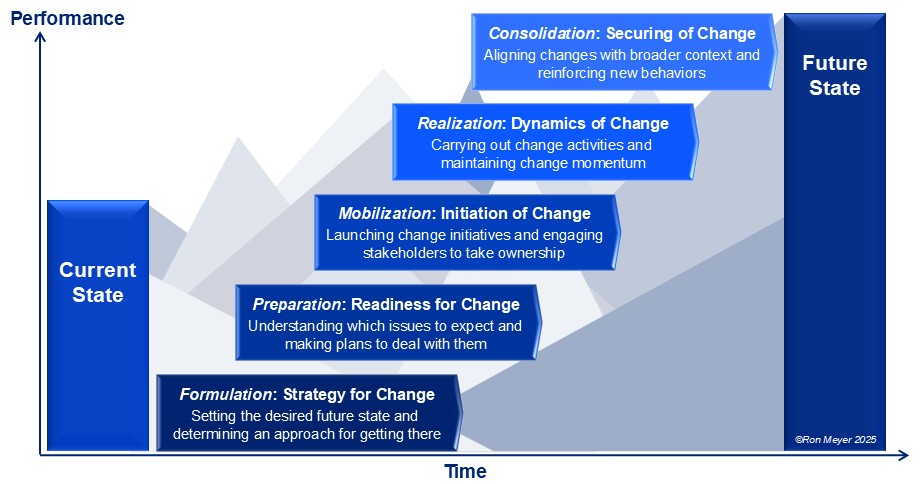

The Five Phases of Change model outlines the five general stages recognizable in any change journey, as the organization moves from the current state through mountainous ups and downs to the desired future state. The five phases overlap along the time-axis, visually conveying the message that a change journey doesn’t take place in neat sequential steps, but that change activities belonging to different phases can sometimes take place simultaneously and that the journey can occasionally even loop back to an earlier phase. The model is intended to be a simple map to plot complex change processes and to help recognize what type of interventions might be required given the phase that the organizational change is in.

Key Elements

The five generic phases of organizational change are the following:

- Formulation: Strategy for Change. The first phase of any change journey is to determine where the voyage is going (change destination), who the voyagers will be (change stakeholders) and how the voyage will take place (change approach). The key challenge is to avoid the ambiguity hazard – the danger of not making clear choices. For a change journey to be successful, the definition of the future state must give a concrete sense of direction, while a viable path for getting there must be set. “We’ll see” is not a strategy.

- Preparation: Readiness for Change. The second phase is to ensure that the organization is ready to embark upon the selected path, by taking away barriers to change (securing change ability) and resistance to change (securing change willingness). The key challenge is to avoid the contracting hazard – the danger of accepting a change strategy for which the organization is not ready. If the organization can’t be made willing and able to follow the selected change path, it might be necessary to loop back and reformulate the strategy.

- Mobilization: Initiation of Change. The third phase is to get the ball rolling, by creating a virtuous cycle of engaging sufficient stakeholders to realize visible changes, thereby building confidence and commitment, that in turn will convince more stakeholders to jump on the bandwagon. The key challenge is to avoid the momentum hazard – the danger of not reaching take-off speed. If too many stakeholders are reluctant to commit themselves to the change journey, tangible results will be lacking, triggering a vicious downward spiral.

- Realization: Dynamics of Change. The fourth phase encompasses all of the actual work of carrying out the required changes. In this, often long, leg of the change journey, the ball needs to keep rolling and a constant stream of activities needs to be completed, while results need to be achieved. The key challenge is to avoid the setback hazard – the danger of suffering a reversal of fortunes, leading people to question the feasibility of the changes. To be successful, organizations need to overcome such blows and carry on.

- Consolidation: Securing of Change. The fifth phase is concerned with making sure that all of the changes are completed, even if resources are running low, people are getting tired and new change projects present themselves as even more urgent. The key challenge is to avoid the anchoring hazard – the danger of not securing all of the realized changes, with people backsliding into old systems and behaviors. Successfully finishing the change journey requires the diligent discipline of tightening up the last nuts and bolts.

Key Insights

- Change journeys are all different. Organizational changes come in many shapes and sizes. They can be broad or narrow in scope (breadth), large or small in scale (height), and rapid or slow in speed (length). Moreover, what is changed and who is involved can vary widely. Therefore, any model of change will necessarily be big picture and generic.

- Change journeys have phases, not steps. Almost all change journeys do not follow orderly steps but are messy, complex processes in which only general phases can be recognized. Yet even these phases can overlap, and looping back can take place.

- Change journeys have five phases. Each organizational change will pass through five phases: Formulation (determining the change strategy); preparation (getting ready to change); mobilization (initiating the change); realization (implementing the various changes); and consolidation (wrapping up and securing the changes).

- Change journeys are hazardous, not straightforward. Change is not only messy but also full of ups and downs, due to the difficulties that must be dealt with along the way.

- Change journeys have five hazards. Each phase has its own key danger that needs to be handled: The ambiguity hazard is the threat of a vaguely formulated change direction; the contracting hazard is taking on a change for which the organization is not ready; the momentum hazard is not reaching take-off speed; the setback hazard of giving up after a disappointment; and the anchoring hazard is not securing the almost completed change.

70. Frictionless Flow Framework

Key Definitions

A customer journey is the path that a potential buyer follows, from first orientation, through purchase and use, to eventually considering follow-up possibilities. It is the entire life cycle of steps that needs to be travelled, from the customer’s perspective. While salespeople often focus on the buying process, the customer journey is the full process experienced by the customer. Firms can influence customers, and create value for them, throughout the voyage.

A pleasing customer journey is sometimes referred to as a happy flow, or frictionless. Customer friction is anything that impedes customers from getting what they want and how they want it. It is any barrier or irritating factor that makes the customer journey less smooth.

Conceptual Model

The Frictionless Flow Framework outlines the six types of customer friction that organizations need to minimize to satisfy (potential) customers. In the top half of the framework, the five generic steps in any customer journey are described, while in the bottom half the six types of friction are detailed. These frictions have been divided into two groups. On the left are frictions that dissatisfy customers because they feel inefficient – they result in some type of loss or pose a risk that a loss will be incurred. On the right are frictions that dissatisfy customers because they feel uncomfortable – they bring the customer in a disagreeable position or pose a risk that this might happen. In all cases, something is a friction if customers perceive it as such. The framework can be used as a checklist to identify specific frictions in any customer journey.

Key Elements

The five generic steps in the customer journey are the following:

- The first step in any journey is to orient oneself. Key questions to be answered are “what is possible?”, “what do I like?”, and “where can I start looking?”.

- Examine. The second step is to determine what you would like to buy. This can involve the evaluation of many options or can be limited to quickly zeroing in on one preference.

- Exchange. The third step is the buying itself. This involves determining how and how much to pay, under which conditions, and how the product/service will be provided to the buyer.

- Experience. The fourth step is to make use of the product/service purchased. This can be quick consumption, but can also be a long process of installing, using, and maintaining.

- Extend. The final step is to consider becoming a repeat customer. This can involve completing the previous use and reflecting on one’s level of satisfaction.

The six types of friction are the following:

- Effort Friction. In our age of instant gratification, the perceived loss of time and energy is felt as irritating. Waiting, needing to provide extensive information, scrolling through incomprehensible menus, and having to come back multiple times, are typical examples.

- Cost Friction. In our age of free wifi, the perceived burden of unnecessary costs is also felt as annoying. Delivery fees, service charges, prepayment requirements and the need to upgrade your IT systems are all examples of needlessly losing money and/or resources.

- Quality Friction. In our age of first time right, it is also frustrating when mistakes are made, and quality is lower than expected. When parts are missing, something breaks too quickly, it isn’t on time or it doesn’t work as promised, we don’t get the anticipated effect or result.

- Uncertainty Friction. In our age of plentiful information, it feels uncomfortable not to know things. A lack of clarity and/or information about when a product will be delivered, whether seats are available, and how a decision will be made, can all lead to a sense of irritation.

- Dependency Friction. In our age of customer choice, it feels uncomfortable to be locked in. A lack of power and/or autonomy to switch to another supplier, change or return an order, use alternative parts, or own your own data, can all be sources of dissatisfaction.

- Unfairness Friction. In our age of corporate social responsibility, it feels uncomfortable to fear being treated wrongfully. Unreadable user agreements, the fine print in a contract, and hiking prices based on your surfing behavior are all examples that undermine trust.

Key Insights

- Customer journeys need to be understood. Firms often map and understand their own internal processes but fail to do the same for the steps that customers go through, even though they can influence the customer’s behavior and satisfaction throughout the journey.

- Customer journeys are full of frictions. Few customer journeys are friction-free, happy flow processes, when looked at from the customer’s point of view. Most are full of irritating barriers and frustrating factors making it difficult for customers to get what they want.

- Customer journeys have economic loss frictions. Some of the frictions lead to (perceived) losses for the customer. They can lose time and energy (effort friction), money and resources (cost friction) and/or effects and outcomes (quality friction). These frictions tend to create dissatisfaction because they are inefficient.

- Customer journeys have emotion discomfort frictions. Other frictions trigger a sense of discomfort with the customer. They can feel ill at ease because they lack clarity and information (uncertainty friction), power and autonomy (dependency friction), and/or trust and justice (unfairness friction). These frictions place customers in an undesirable position.

- Customer journeys require continuous improvement. When firms consider ways of strengthening their competitive advantage, they often turn to upgrading their product/ service. Yet, improving the customer journey by removing frictions (friction hunting) is also a powerful way to compete. But it requires continuous work on the entire journey.

Key Definitions

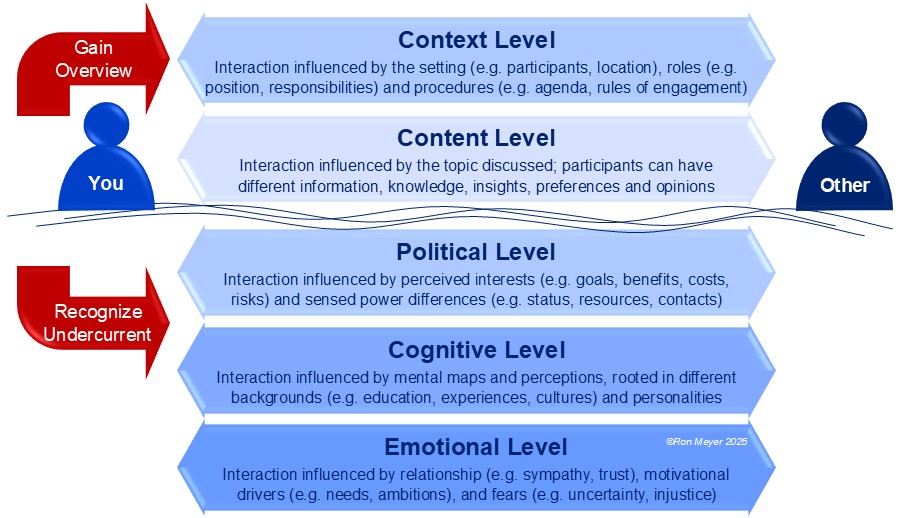

Managers and employees interact with each other and with the outside world on a daily basis – they talk, discuss, argue, laugh, decide, plan, check in and fight, not necessarily in that order. They interact one-on-one, but also in groups, and for a variety of reasons.

Interaction between people is so normal, that we hardly realize that every interaction is unique and is shaped by a wide range of influencing factors. Some of these interaction drivers are fixed but some can be adapted, which can significantly change the interaction dynamics.

Conceptual Model

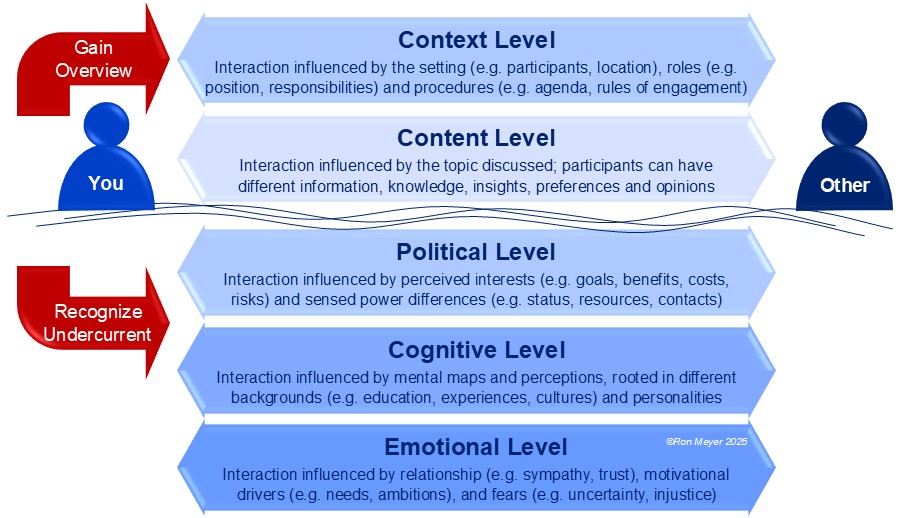

The Interaction Drivers framework outlines the five levels of influencing factors that determine how an interaction between two people takes place. Most people will interact with each other around a particular topic (the content level), but the way they interact will be governed by some overarching circumstances (the context level). At the same time, under the surface, the interaction will be impacted by political, cognitive, and emotional factors on both sides. The framework is intended to help people understand what is driving their interactions, making them aware that they shouldn’t only focus on the content being discussed, but need to zoom out to understand how various context factors are shaping behaviors, while at the same time acknowledging the powerful influence of the undercurrent.

Key Elements

The five levels of interaction drivers are the following:

- Content Level. This is the level of the topic itself – what people believe they are interacting about. Obviously, talking about last night’s game will be a different type of interaction than discussing the poor sales numbers, arguing about the next elections, or deciding where to place the new coffee machine. In each case, people can have different levels of information and knowledge, varying insights and evaluations, and diverging preferences and opinions.

- Context Level. If you could hover over two people interacting, you could see how their behavior is shaped by various conditions, such as the setting (in the office or the bar, with just two people or a whole team) the timing (on Monday morning or Friday afternoon, in January or tomorrow), their roles (between colleagues or with your boss, with a problem owner or the doorman) and procedures (with or without an agenda and meeting rules).

- Political Level. While the context factors are out in the open, the political factors shape the interaction under the surface. People will have different interests (striving for different goals and benefits, while avoiding various costs and risks), but will also have a perception of the interests driving their counterpart. At the same time, both sides will have an estimation of their own level and sources of power vis-à-vis the other.

- Cognitive Level. Even deeper under the surface will be the divergent worldviews shaping what people say and do. Both sides will have different mental maps, formed by their unique set of experiences, educational backgrounds and cultural heritage, but also by different personalities, all contributing to a different way of interpreting what is going on. People are usually unaware of the lens they look through, assuming the way they think is “normal”.

- Emotional Level. At the deepest level, interactions will be shaped by both sides’ emotions, such as how they feel about the other (do they like and trust the person?), their motivations (what are their needs and ambitions?) and their fears (are they worried about what might happen or being treated unfairly?). People often lack enough emotional intelligence to recognize their counterpart’s feelings, but also to recognize and understand their own.

Key Insights

- Interactions are shaped by a range of drivers. Each simple interaction between people is determined by a complex array of influencing factors, making each interaction essentially unique. Therefore, understanding why both sides of an interaction behave in the way they do, can be difficult. The Interaction Drivers framework helps with this task.

- Interactions are shaped by content factors. When people interact, it is generally around some topic or issue. The type of subject will have a huge impact on how they interact – talking about the weather will be different than deciding on a big investment. But also, people’s information, knowledge, insights, preferences and opinions will be important. All these content factors tend to be on the surface and therefore relatively easy to recognize.

- Interactions are shaped by context factors. Every content interaction is also governed by a variety of interaction conditions, such as the setting, the timing, the participants’ roles and the procedures to which they adhere. These context factors are often not directly recognizable on the surface but require the observer to zoom out to see them.

- Interactions are shaped by undercurrent factors. At the same time, there are always factors under the surface shaping people’s attitudes and thereby impacting their interactions. These undercurrents are people’s political considerations (their interests and power), their cognitive filters (their mental maps and personalities) and their emotional drivers (their feelings towards each other, motivations and fears).

- Interactions can be understood and adapted. The Interaction Drivers framework can be used afterwards to make sense of a past interaction, or during an interaction to understand what is happening. But ideally, the framework can be employed to anticipate a future interaction and to adjust one’s approach ahead of time to get the best possible outcome.

68. Innovation Sins & Virtues

Key Definitions

Innovation is the act of doing something new and distinctive. Firms need to constantly try to innovate their products/services, processes and even business model, to improve their value creation and strengthen their position vis-à-vis competitors.

Being innovative is not a quality that happens naturally or by accident, but a capability that needs to be organized. A one-off innovation can happen despite a lack of structural innovation capability, but ongoing innovation requires the buildup of the right organizational conditions.

Conceptual Model

The Innovation Sins & Virtues framework identifies the seven most deadly sins in the area of innovation. Each undermines an organization’s capability to continuously innovate and condemns it to linger in ‘innovation hell’. Each sin can be avoided by adhering to its opposite virtue. Together these seven vital virtues create the organizational conditions necessary to achieve ‘innovation heaven’. The framework is intended as a checklist to evaluate an organization’s current innovation infrastructure and to suggest avenues for improvement.

Key Elements

The seven sets of opposite sins and virtues are the following:

- The Exploitation Trap vs. The Exploration Imperative. In the short run, it is financially more attractive to invest in optimizing the organization’s current products and processes, than to place bets on inherently more risky innovation projects. So, management teams often fall for the lure of exploiting what they already have, instead of having the courage to venture out into the unknown to explore innovative opportunities. But explore they must.

- The Icarus Syndrome vs. The Insurgency Mindset. Organizations also get stuck in the past because they come to believe that their historic success formula will remain the recipe for profitability in the future. But to be innovative, organizations need to be irreverent rebels, looking for ways to smash the past and come up with a challenging alternative. They need to be willing to upset their business themselves, instead of letting others do it to them.

- The Big Bang Fallacy vs. The Marathon Mantra. Innovation is not an event, but a process. It doesn’t happen in a short sprint but requires years of hard work. Yet, many managers think of innovation as an occasional occurrence that takes place suddenly and radically, after which a long stretch of stability sets in. But, of course, innovation is more like a marathon, requiring sustained dedication and discipline to reach the finish line.

- The Innovation Monastery vs. The Innovation Bandwagon. The R&D department can be a key source of new technology and novel ideas, yet they are often far removed from operations and the market, which can make their thinking rather one-sided, even esoteric. Successful innovation requires a variety of skills and perspectives, making it an organization-wide activity. And novel ideas can come from anywhere in the organization.

- The Business Bulldozer vs. The Business Incubator. Although everyone in the organization can get involved in innovation, new initiatives need to be shielded from everyone imposing their existing policies and procedures on the infant innovation. ‘Business as usual’ often unintentionally smothers the unusual new approach. Therefore, innovations need to be kept at a distance and incubated in the best suiting circumstances.

- The Lone Inventor Legend vs. The Capability Condition. The stories told about aspiring innovators starting their new company in a garage has led many people to believe that true entrepreneurs don’t need any support and even thrive on adversity. Unfortunately, the lone inventor is the exception, not the rule. To increase the chance of success, organizations need to create supportive conditions, including sufficient time, resources and infrastructure.

- The Fermentation Fable vs. The Mobilization Missionary. In the same way, many top managers believe that innovations will bubble up from lower in the organization, driven by dogged individuals. In reality, the more that top management promotes innovation, the higher the chance of eventual success. At the very least, top managers need to provide air cover for challenging new initiatives, but even better is for top managers to be the advocates of innovation in general and to champion certain innovations in particular.

Key Insights

- Innovation doesn’t come naturally. How to be innovative is poorly understood by most managers, while there are many innovation pitfalls into which they can easily tumble.

- Innovation is hindered by seven deadly sins. There are seven common dysfunctional behaviors undermining organizations’ capability to innovate – focusing on exploitation, clinging to past successes, hoping for a sudden change, leaving innovation to R&D, imposing existing procedures, giving little support, and providing no management backing.

- Innovation is supported by seven vital virtues. Each deadly sin can be avoided by sticking to a vital virtue – embracing exploration, challenging success formulas, taking a structural approach, involving the whole organization, sheltering innovations from standard procedures, providing organizational support, and getting top managers as champions.

- Innovation stuck between heaven and hell. Few organizations live all seven virtues all the time. But this framework can be used as a checklist to evaluate how well they are doing.

- Innovation needs to be organized. The conclusion is that to be innovative requires innovation management – a structured approach to abide by the seven vital virtues.

Key Definitions

Firms often seek to grow their top line, i.e. their gross revenue derived from the sale of goods and/or services. In a now famous paper, Igor Ansoff (1957) argued that such growth can be pursued along two dimensions – in existing and new markets, and with existing and new products. The resulting 2x2 diagram is widely known as the Ansoff Matrix.

Ansoff’s four growth directions are market penetration (more existing products in existing markets), market development (more existing products to new markets), product development (new products to existing markets) and diversification (new products to new markets).

Conceptual Model

The Top Line Growth Pie builds on Ansoff’s logic of seeking growth along the dimensions of product and market, but splits each category into smaller parts, to give strategists a more fine-grained view into the various growth possibilities. Along the market dimension (plotted horizontally), a distinction is not only made between existing (at the center) and new (around the center), but also between new segments and new geographies. Each is further split according to the extent of newness – adjacent or distant. Along the vertical product dimension, the same is done, making a distinction between new products in or outside the existing business. The underlying metaphor is that firms can grow by taking a bigger slice of the existing pie (increase market share) but also have nine ways of taking a piece of a much larger pie.

Key Elements

The ten growth directions are the following:

- Increase Market Share. Taking more of the existing pie means finding ways to lure customers away from competitors, or even to acquire these competitors altogether. For example, a bicycle manufacturer could advertise more to gain additional market share.

- Increase Market Size. The existing pie can be grown by getting existing customers to buy more products and/or by finding more potential customers willing to adopt the product. So, a bicycle firm could try to get more people to cycle and/or get them to buy a second bicycle.

- Expand to Adjacent Segments. Growth can also be found in neighboring customer groups not traditionally served, but with a similar needs profile and buying behavior. So, a bicycle firm could start selling to pensioners and/or people trying to lose weight.

- Expand to Distant Segments. More difficult is to seek sales among customer groups with rather different characteristics in terms of needs and buying behavior. So, it might be a challenge for a bicycle firm to start selling to health clinics and/or courier firms.

- Expand to Adjacent Regions. Growth can also be sought among customers in cities, states, or countries with a low psychological distance from the current markets. So, a bicycle firm in Amsterdam could start selling in Rotterdam or even in Belgium or the UK.

- Expand to Distant Regions. A quick sale in a faraway place can be easy, but it is more difficult to build a structural market position where the rules of the game are very different. So, it would be tough for an Amsterdam-based bicycle firm to establish itself in Dubai.

- Product Range Extension. By adding new products/services to the product family already being sold, new customers can be found, or existing ones might be willing to buy more. So, introducing e-bikes and mountain bikes could be a great way for a bicycle firm to grow.

- Value Proposition Enhancement. Beyond extending the core range, the envelop of linked products, services, information, distribution, reputation, and payment features can be expanded. So, leasing bicycles including regular servicing could be a great growth avenue.

- Related Diversification. Existing competencies and/or relational resources (e.g. contacts and reputation) can be leveraged to enter new lines of business. So, a bicycle firm could branch out into exercise equipment and/or cycling clothing.

- Unrelated Diversification. Firms can also expand into totally new businesses, leveraging little else than their financial resources, management knowledge and business ideas. So, a bicycle firm could jump on the AI bandwagon and start selling translation software.

Key Insights

- Top line growth is about a bigger slice and/or a bigger pie. To most firms, growing their sales is important. Therefore, it is essential to see that growth can be realized by taking market share away from competitors (a bigger slice), but that there are also nine ways to expand their range of sales opportunities beyond the current, taking a slice of a bigger pie.

- Top line growth can be found in market development. Firms can expand to new customer groups (market segments), both close to their current ones and further afield. Equally, they can branch out to new regions (geographic markets), both close and afar.

- Top line growth can be found in product development. Firms can grow by broadening their product range, but also by broadening the value proposition, to include supplemental products/services, and/or extra information, distribution, reputation, and payment features.

- Top line growth can be found in business development. Firms can also grow outside their current lines of business, to related areas where they can leverage existing competencies and/or relational resources, or to totally unrelated areas.

- Top line growth thinking can be helped by retiring Ansoff. There is nothing inherently wrong with the Ansoff matrix, but as a thinking tool it is of limited value, because it fails to offer a fine-grained enough insight into the variety of growth directions that firms have open to them. So, after 68 years of loyal service, it is time to retire the Ansoff matrix.

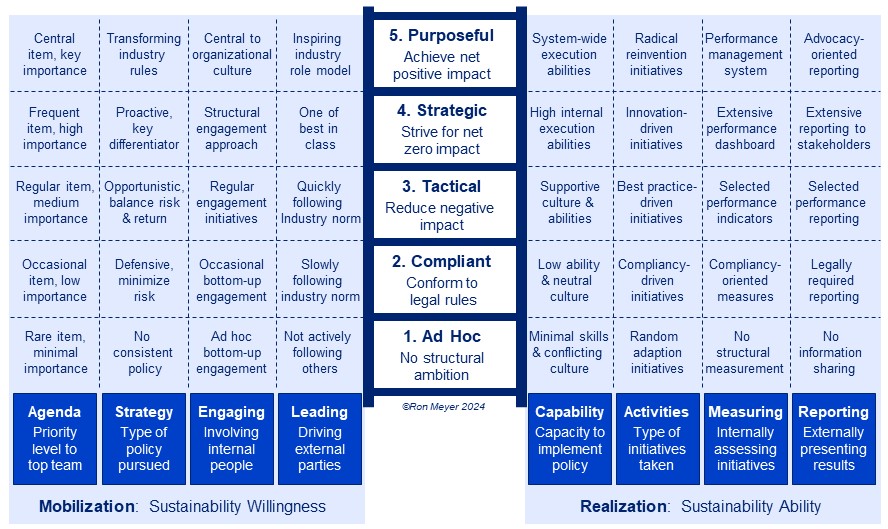

66. Sustainability Maturity Ladder

Key Definitions

A product or practice is sustainable if it can be continued over a longer period of time without depleting natural or social resources. So, sustainability is the quality of engaging in current activities in such a way that future possibilities are not diminished.

Organizations have always been concerned with their own sustainability, wanting to ensure their survival as a business or a not-for-profit actor. But more recently, organizations have paid increasing attention to the sustainability of their surroundings, given the organization’s impact on the environment and society (the indirect consequences that economists call externalities).

Conceptual Model

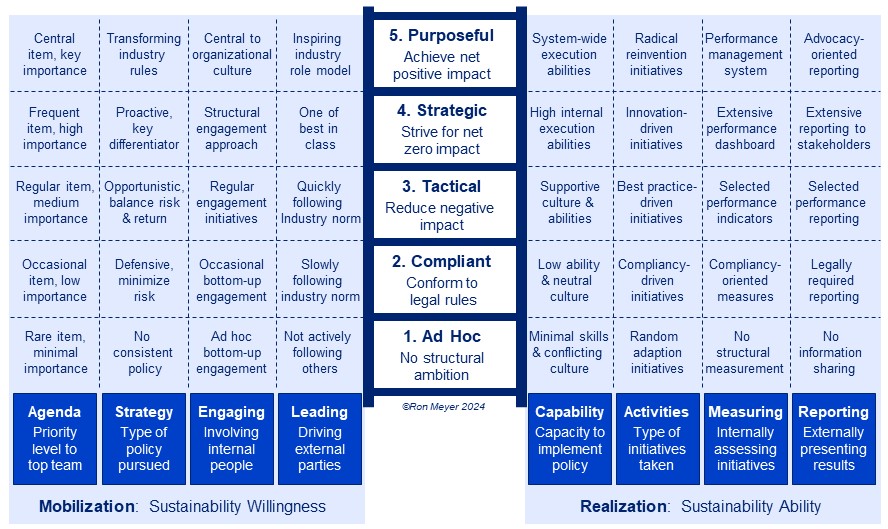

The Sustainability Maturity Ladder outlines the five levels of sustainability that organizations can achieve. Typically, organizations will progress through each level as a developmental stage, gradually climbing the ladder to become more mature as sustainable organization. The framework details the characteristics fitting to each stage, although in practice organizations will not neatly fall into these five categories, nor go through all stages in the same way and at the same speed. The framework is intended to help organizations map where they stand and suggest what a next development step could be.

Key Elements

The five development levels on the ladder are:

- Ad Hoc Level. At the lowest level, sustainability is not an issue that receives structural attention, but a rare topic that is reactively dealt with on a case-by-case basis.

- Compliant Level. Once sustainability gets on the radar screen, it is seen as a nuisance that needs to be managed. Organizations minimize risk by sticking to the legal rules.

- Tactical Level. As organizations realize their responsibility for externalities, they will make regular efforts to reduce their negative impact, as long as it doesn’t hurt their core business.

- Strategic Level. Once organizations embrace the ambition to be fully sustainable and have a net zero impact, it becomes a central plank of their strategy and key to their identity.

- Purposeful Level. At the highest level, organizations can strive to be more than sustainable, making it part of their organizational purpose to give back more than they take.

Each of these five development levels has eight distinguishing characteristics:

- This refers to the extent to which sustainability is seen as a topic with which top management needs to be actively involved. How high is it on the boss’s to-do list?

- With what type of approach does top management react to the topic of sustainability? Do they see it as threat or as opportunity?

- Engaging. To what extent is sustainability an issue that involves of a large portion of the organizational population? Is it a rallying cry that mobilizes internal people?

- Leading. How does the organization position itself vis-à-vis other organizations on the topic of sustainability? Does it want to follow or lead external parties?

- Capability. To what level has the organization developed the skills and culture necessary to be sustainable? Does the organization have the ability to behave sustainably?

- Activities. How advanced are the types of sustainability initiatives that the organization implements? Are the interventions conventional or more innovative?

- Measuring. How sophisticated is the internal system for assessing sustainability performance? To what extent can the organization track and trace how well it’s doing?

- Reporting. How sophisticated is the system for externally publicizing sustainability performance? In what way does the organization present its results to the outside world?

Key Insights

- Sustainability is about safeguarding future potential. To act sustainably is to ensure that an organization’s impact on its environmental and social surroundings doesn’t diminish future possibilities for the organization and others. It’s about not running things down.

- Sustainability can be approached at five different levels. Organizations can engage with the topic of sustainability at five levels of intensity, varying from a standoffish attitude to fully embracing its central importance. Organizations can react haphazardly (ad hoc level), defensively (compliant level), opportunistically (tactical level), proactively (strategic level) and idealistically (purposeful level).

- Sustainability levels differ with regard to willingness to be sustainable. The five levels can be differentiated based on how each takes a different approach to mobilizing people to deal with sustainability. They differ in how high the topic is on the agenda, the type of strategy pursued, how internal people are engaged and how external people are led.

- Sustainability levels differ with regard to ability to be sustainable. The five levels can also be distinguished by the organization’s ability to realize sustainable behavior. They differ in what type of capabilities have been developed, what type of activities are carried out, how performance is measured internal and reported

- Sustainability levels are the rungs on a maturity ladder. Some organizations have started at a high level, but most are in the process of gradually climbing the ladder to a higher level of sustainability maturity. However, this evolution differs wildly by organization.

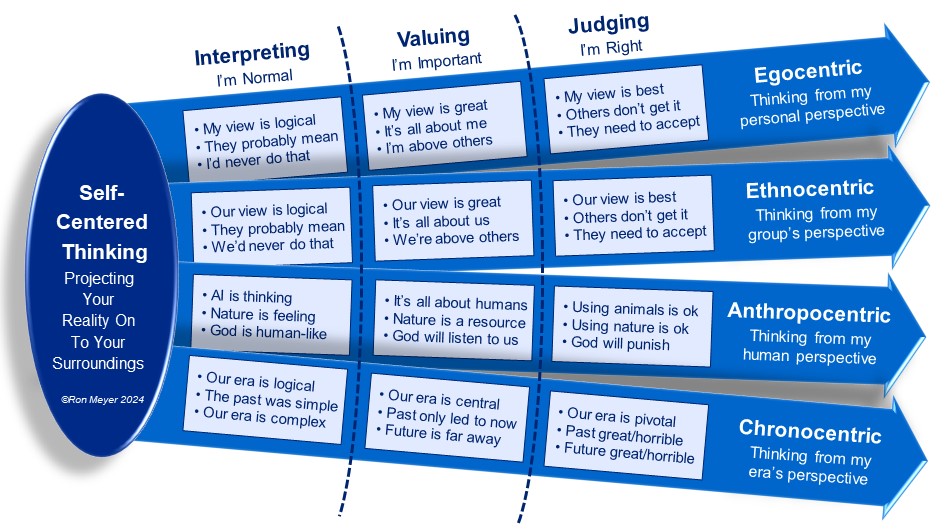

65. Self-Centered Thinking Traps

Key Definitions

Reasoning is the process of thinking and drawing conclusions from information based a particular type of logic. As this logic is specific to each individual, it is also called a person’s worldview, frame of reference, cognitive filter, perceptual lens, or perspective.

People’s perspective develops over their lifetime, depending on their surroundings and experiences. It is formed by what they encounter as individuals, as members of a group, as humans and as living in the current era. But while circumstances shape people’s perspective, that perspective in turn shapes how people see their circumstances.

Conceptual Model

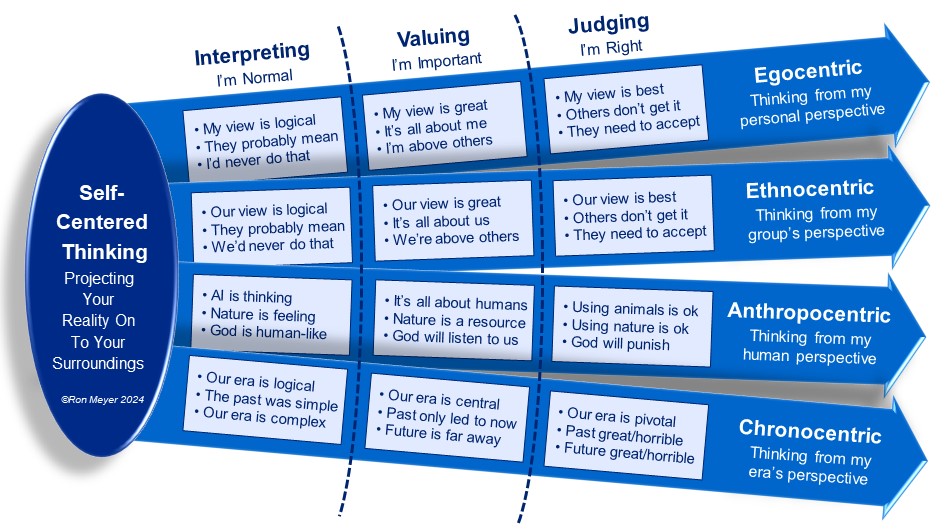

The Self-Centered Thinking Traps framework outlines the four most common ways in which people’s narrow self-centered perspectives can lead to shortsighted conclusions. These four ways of thinking are all based on people’s inherent tendency to place themselves at the center of the world and then to project their reality on to their surroundings. By predominantly viewing matters from their own perspective, they draw highly colored, one-sided conclusions, that would be different if they could see things from multiple perspectives. The framework identifies four types of self-centeredness (the blue arrows) and three types of reasoning (interpreting, valuing, and judging), and gives 36 examples of shortsighted conclusions that are often drawn.

Key Elements

The three types of reasoning are the following:

- The first step in reasoning is to try to make sense of reality. Self-centered thinkers will assume that they are normal and understand the world from that viewpoint.

- A step further than determining what is valid, is weighing what should be valued. Self-centered thinkers will assume that they are more important than anything else.

- Judging. The last step in reasoning is to draw conclusions and pass judgement. Self-centered thinkers will assume they are right and proceed accordingly.

The four types of self-centered thinking are:

- Egocentric Thinking. Reasoning from your own personal perspective is the most recognized form of self-centered thinking. Individuals will believe they are normal and assume that others think in the same way (‘they probably mean…”), or at least should think in the same way. They can even value themselves above all others, favor their own interests and look down on people who “don’t get it”.

- Ethnocentric Thinking. Reasoning from a group’s perspective comes in many forms, as people are members of many groups. People will take the perspective of their national culture as obvious, not understanding or valuing other cultures. But they can also view matters through the lens of their ethnic group, social class, gender, club, region, company, and/or department. The more they interact within their group, the stronger their bias will be.

- Anthropocentric Thinking. Maybe less obvious is the tendency of people to view reality from the perspective of being a human. People will assume that other things “think” in a human-like way (e.g. animals, AI, God) and that humans are more important than anything else, justifying human’s central role in the world. The consequences can vary from treating a dog like a human baby to accepting that humans have the right to create climate change.

- Chronocentric Thinking. The least obvious is the tendency to view reality from the perspective of our current era. People constantly reinterpret history through the lens of modern times, not understanding how our ancestors could be so foolish and retroactively condemning their behavior, or alternatively, glorifying the past. In the same way, people project today into the future, predicting impending doom or imminent greatness.

Key Insights

- Reasoning is inherently subjective. Reasoning is a train of thought that leads to a conclusion. This thinking can’t be objective as people view the world from a specific perspective – through a lens that we have built up during our life, based on our experiences.

- Reasoning comes in three forms. People use this lens to interpret the information they receive (i.e. sense-making), to place value on themselves in the situation (i.e. determining importance) and to judge what the consequences should be (i.e. decision-making).

- Reasoning is full of hidden traps. The lens that people use will always color what people see. So, if people have only one highly colored lens, their reasoning is going to be highly biased. The danger is that they will not be aware of their own slanted perspective.

- Reasoning can be dangerously self-centered. The most common form of bias is reasoning from one’s own perspective – called self-centered thinking. People can think from their personal perspective (egocentric thinking), from their group’s perspective (ethnocentric thinking), from their human perspective (anthropocentric thinking) and from their era’s perspective (chronocentric thinking).

- Reasoning can be enriched by multiple perspectives. To avoid these self-centered thinking traps, people need to reflect on their own thinking, to open up to feedback on their thinking and to practice using multiple perspectives to be able to see matters from different angles. Of course, engaging in dialogue with people who have a different perspective is probably the most valuable approach, if it is true dialogue and not debate.

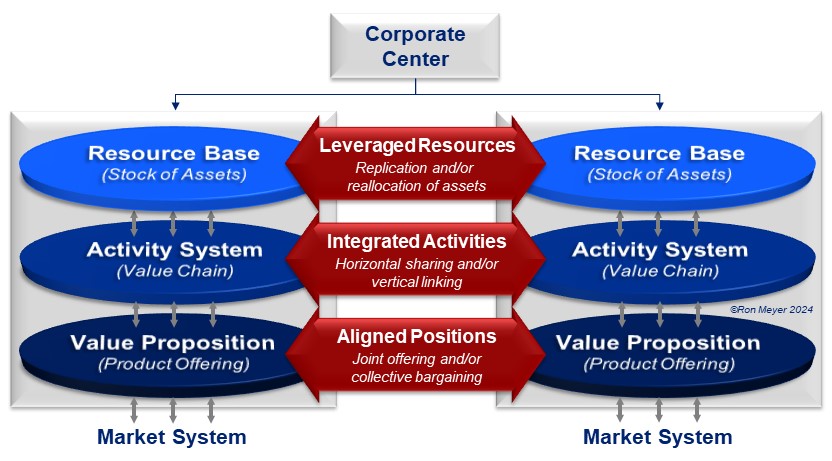

64. Corporate Synergy Typology

Key Definitions

There is synergy when the whole is more than the sum of the parts – when bringing together two or more elements leads to the creation of something extra. In organizations, we speak of synergy when operating in two or more markets leads to additional value, that wouldn’t be realized if the organization had focused on only one task environment.

Organizations can strive for cross-business synergies by working in more than one product market (different lines of business) and cross-border synergies by working in more than one geographic market (different countries or regions).

Conceptual Model

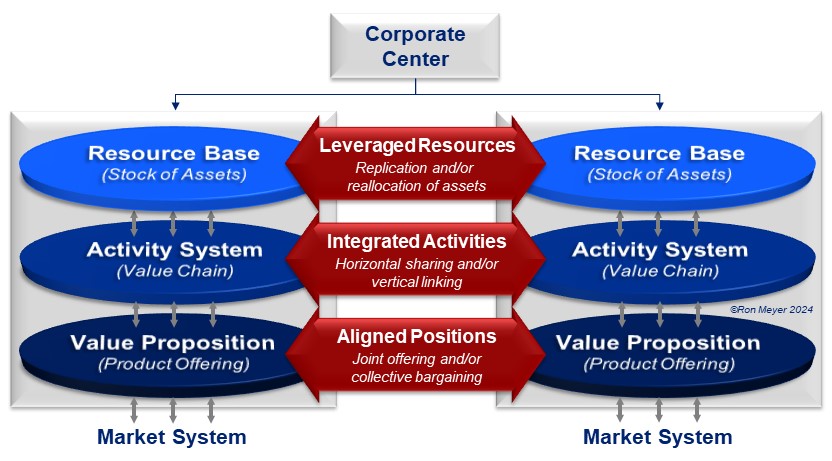

The Corporate Synergy Typology outlines the three types of synergies that organizations can create (in red). In this model only two business units are used to illustrate the three types, but these synergies can also be realized across more than two units. The synergies are found between the three layers of each unit’s value creation system (usually called their business system – see model 47, the Corporate Strategy Framework for an overview). Organizations can focus on just one synergy or pursue them all simultaneously. In general, the closer the synergy is to the market, the more difficult it is to realize. How the synergies need to be organized is not addressed in this model (see model 8, 11C Synergy Model).

Key Elements

The three types of synergies are the following:

- Leveraged Resources. Each business unit has a variety of resources at its disposal that it employs as inputs for its activity system. These resources include tangible assets such as buildings, machines, and money (basically everything on the balance sheet), as well as intangibles such as knowledge, capabilities, data, and relationships. These resources can be leveraged across business units in two different ways:

- Replication. Most intangibles, like best practices, can be copied and transferred to other business units without the owner losing the resource.

- Most tangibles, like money, can’t be copied, but need to be partly or fully moved from one business unit to another, where their use will be more valuable.

- Integrated Activities. A business unit needs resources to perform a variety of activities that will result in a value proposition. These value-adding activities include primary activities like production and sales, support activities like finance and R&D, and control activities like legal and risk management (see model 50, Activity System Dial). These activities can be integrated across business units in two different ways:

- Horizontal sharing. Business units can bring similar activities together to create economies of scale and/or develop more expertise (horizontal integration).

- Vertical linking. Business units at different steps in the industry value chain can link up to improve efficiency, quality, speed and/or market power (vertical integration).

- Aligned Positions. A business unit’s reason for existence is to bring a product or service to market that customer will prefer to purchase. To achieve this, it needs to select a defensible market position – a specific customer need that it can satisfy with a fitting value proposition, better than competitors. This position in the market can be strengthened when business units work together in one or both of the following ways:

- Joint offering. Negotiation power vis-à-vis the customer can be increased by offering an aligned portfolio of value propositions or even an integrated solution.

- Collective bargaining. Negotiation power vis-à-vis other market and contextual actors can be increased by aligning influencing efforts (see model 31, Market System Map).

Key Insights

- Synergies are created between two or more business units. To some people, ‘realizing synergies’ sounds like a euphemism for cost savings. But although reducing cost can be the advantage sought, synergies can also lead to increased expertise, higher speed, better quality, and/or more market power. A synergy is any additional value that is created when two or more business units work together instead of separately.

- Synergies are created between business systems. Each business unit creates value by taking inputs (it’s resource base) to perform a variety of coordinated tasks (it’s activity system) to produce an output (it’s value proposition) that can be brought to a specific market. Together, this value creation approach is called the unit’s business system. Synergies can be realized by building bridges between various business systems.

- Synergies can be created at three different levels. Synergies can be achieved by leveraging resources across units, integrating activities between them, and/or aligning positions they have in the market. All can be realized separately or simultaneously.

- Synergies are created at the expense of responsiveness. To accomplish synergies, units need to work together, which can slow them down and require compromise. So, pursuing synergy can cut into units’ ability to be responsive to market needs. Therefore, the selected synergies need to be more valuable than the loss of responsiveness.

- Synergies also need to be organized. Synergy is the value derived from working together, but this collaboration needs to be structured and managed in a smart way.