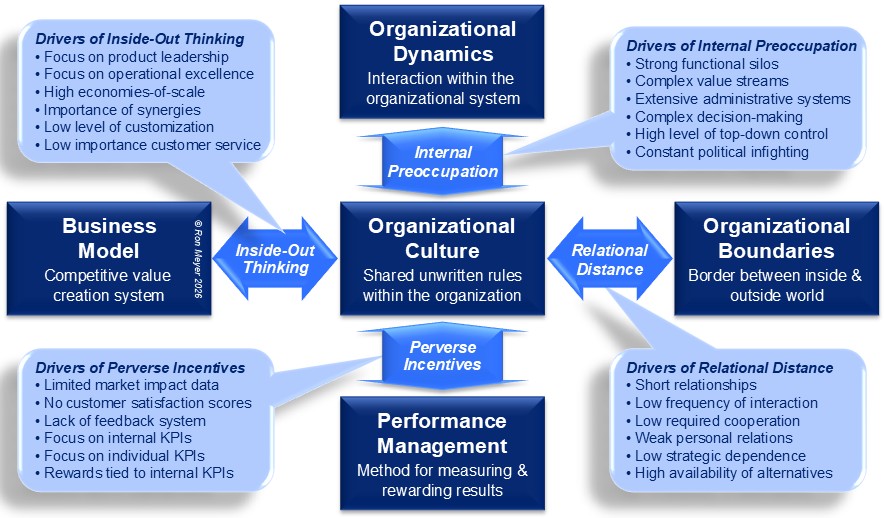

80. Five Company-Centric Forces

Key Definitions

When it comes to their culture and behaviors, organizations can be more outward-oriented, focused on responding to the demands in their external environment, or more inward-oriented, concentrated on dealing with the complexities of their internal environment.

For companies, the ultimate form of outward-orientation is customer-centricity – placing the external customer at the center of everything done internally. The opposite can be called company-centricity, whereby people in the organization pay little attention to the outside world but direct their time and energy at coping with internal processes, interests and interactions.

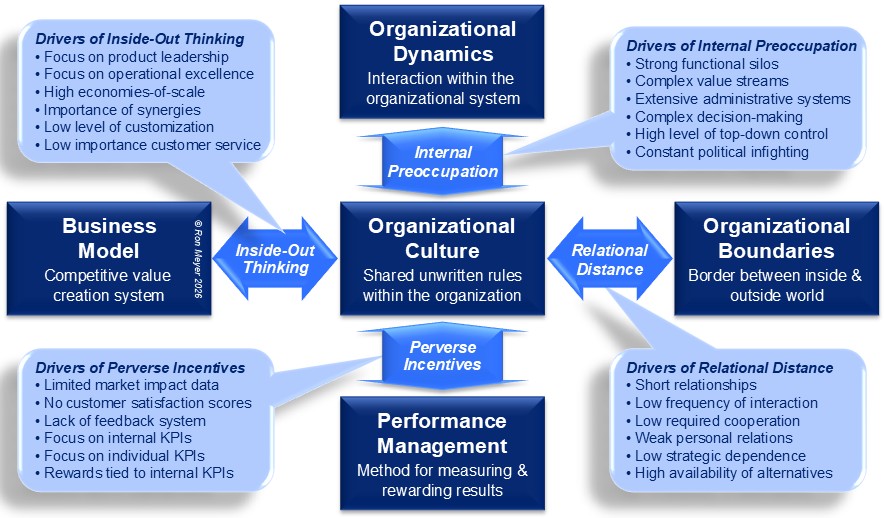

Conceptual Model

The Five Company-Centric Forces model is an analytical framework for understanding the factors pushing organizations towards inward-orientation. This model is an explicit homage to Porter’s Five Competitive Forces model (1979), that outlined the five external challenges that companies need to contend with to be successful. The Five Company-Centric Forces model outlines the five internal challenges facing companies that draw them towards self-involved inward-orientation, thereby undermining these organizations’ focus on competing externally. The model can be used to uncover the specific drivers of company-centricity in an organization, as a first diagnostic step before taking initiatives to enhance outward-orientation.

Key Elements

The five company-centric forces are the following:

- Organizational Culture. At the center of the model is an inward-oriented culture, that values organizational, departmental or even individual views and interests above those of the customer. Like an ego-centric person, company-centric people believe their worldview is the correct one and they know what good looks like. Dealing with each other is also seen as more important than dealing with customers. Once this culture of self-involvement takes root, it becomes self-perpetuating and can be further strengthened by the other four forces.

- Business Model. The type of business model chosen can influence how much outward-orientation people believe is necessary. Companies competing on personalization and customer service need to think outside-in, while competing on product leadership, operational excellence, economies-of-scale and capturing synergies push people to think inside-out and concentrate on internal processes. The more the inside-out thinkers capture attention and can claim success, the more a culture is nudged towards inward-orientation.

- Organizational Boundaries. Companies often create strong organizational boundaries by keeping their distance from customers. They interact and cooperate infrequently, and avoid personal and long-term relationships, either because they don’t want to, or don’t have to. Keeping customers at arm’s length is generally easier where dependency on customers is low and there are plenty of alternatives. Yet, distance invariably leads to less understanding of, and interest in, customers, thereby reinforcing an inward-oriented culture.

- Organizational Dynamics. Companies can also become intensely preoccupied with their own processes and procedures, which shows up in extensive meeting schedules and reporting systems. Strong silos are by nature inward-oriented, but if they need to coordinate because of complex value streams, procedures and meetings proliferate. Self-involvement is further strengthened by complicated decision-making, political games and top-down controls. When employees are busy with each other, they’re not busy with the customer.

- Performance Management. Finally, companies often measure and reward the wrong type of results. Instead of tracking market impact data and customer satisfaction feedback, companies often use internal performance indicators, typically at the level of a department or individual, encouraging employees to shortsightedly focus on their own work. Where recognition and rewards are linked to these internal, instead of external, results, a perverse incentive is given to become even more inward-oriented and ignore customer satisfaction.

Key Insights

- Company-centricity is extensive inward-orientation. Organizations, like people, find it much easier to understand and be busy with themselves, instead of with others. This inward-orientation, as opposed to outward-orientation, comes in various shades of grey, with at its extreme a far-reaching form of self-involvement called company-centricity.

- Company-centricity is at its heart cultural. Company-centricity is a mindset common to people in an organization, leading to typical behaviors and ways of working. In other words, company-centricity is cultural – unwritten norms based on shared values and beliefs.

- Company-centricity is driven by five forces. A company-centric culture is self-perpetuating and can be reinforced by four other factors: A business model that emphasizes the importance of inside-out thinking, strict organizational boundaries that lead to relational distance, complex organizational dynamics that trigger internal preoccupation and a performance management approach that creates perverse incentives.

- Company-centricity grows over time, if unchecked. These five company-centric forces drive a vicious cycle, gradually decreasing awareness of, and interest in, customers.

- Company-centricity needs to be understood to be countered. The Five Company-Centric Forces model is an analytical framework for understanding the factors causing company-centricity, thereby suggesting places to start building more customer-centricity.

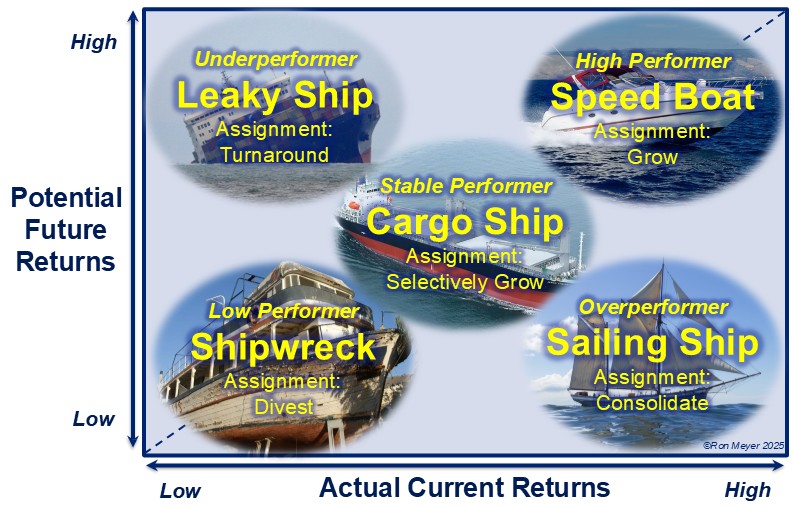

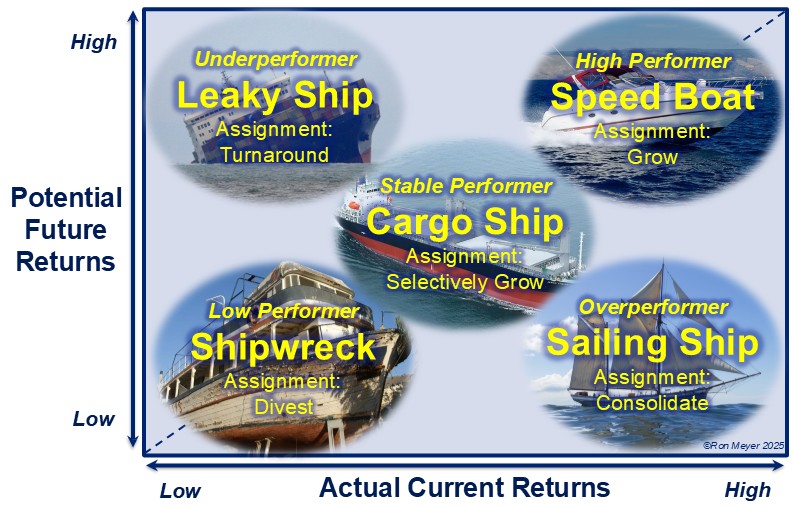

79. Strategic Assignment Matrix

Key Definitions

A corporation has a portfolio of business units when it consists of two or more operating companies, each requiring a separate strategy because they compete in different markets.

While each business unit will typically strive to have a unique competitive strategy, the corporate center will give them a more general strategic assignment to grow, consolidate, turnaround or leave. Corporate investment in each business unit, and the expected future performance, will all be aligned with this specific strategic assignment.

Conceptual Model

The Strategic Assignment Matrix is an analytical framework for setting the overall strategic objective for each business unit in a corporate portfolio. It is based on a comparison between the current returns achieved by each unit and their potential future performance. The current performance, however measured, is known for each unit, allowing each to be plotted on the horizontal axis, with the expected average return in the middle. Then an analysis of each unit’s potential future performance needs to be made, based on a projection of market attractiveness and the unit’s competitive strength. The resulting position on the vertical axis is both an analytical estimation and a tangible future target. The outcome for each unit will be one of five strategic assignments, with linked room for investment. Ideally, the analysis and conclusions should be jointly agreed on by the corporate center and business units.

Key Elements

The five possible strategic assignments are the following:

- Grow: For High Performing Speedboats. Any business unit that is currently reaching above average returns and has a realistic possibility to keep on achieving superior performance in the coming years, has earned the right, but also has the duty, to invest in further growth. Their assignment will be to realize their potential, by increasing their topline and/or margins in a way that is sustainable in the longer run.

- Selectively Grow: For Stable Performing Cargo Ships. Business units with healthy returns and the prospect of staying that way for the foreseeable future, need to selectively bet on growth opportunities, while keeping their base business stable and up to date. Their assignment will be to stay in shape, by prudently investing in improvements and renewal, to keep their returns on par.

- Turnaround: For Underperforming Leaky Ships. Achieving lower than average returns is a clear indication that the business unit has sprung a leak. It can be an old vessel that hasn’t been properly maintained, or a new one with some start-up challenges. If the future potential is still positive, investments should be made to rapidly turn the situation around. The assignment will be to quickly plug the leak and prove the ship is still seaworthy.

- Divest: For Low Performing Shipwrecks. If the future potential of a poorly performing business unit is unattractive, then investing to plug leaks will not suddenly make a shipwreck seaworthy. Valiantly investing in a sinking ship will only suck the captain down with it. The assignment will be to decisively withdraw from the business, often by divesting it to another shipyard or even by dismantling it, to salvage some reusable parts.

- Consolidate: For Overperforming Sailing Ships. Some business units are like old sailing ships; they’re still operating well, but they’re not the ships of the future. As their longer-term potential is limited, selective investments should be focused on maintenance and sustaining the existing business. Their assignment will be to prolong their lifespan, getting as much mileage out of the existing resources and relations as possible.

Key Insights

- Strategic assignments are about future investments. In a corporation with two or more business units, the corporate center must decide like a financial investor in which parts of the portfolio to inject capital, which to hold and which to divest. But while an outside investor can only passively allocate capital, the corporate center can actively assign units the objective to grow, consolidate or exit the business.

- Strategic assignments depend on current and future performance. When determining which assignment to give each unit, the corporate center will contrast how well each unit is currently performing, which is known, with its future performance potential, which needs to be analyzed by considering the future market attractiveness and the unit’s potential competitive position. Current and future performance potential are plotted in the matrix.

- Strategic assignments come in five flavors. The five generic strategic assignments are grow, selectively grow, turnaround, divest and consolidate. Each assignment provides a business unit with the general direction on which to base their detailed business strategy.

- Strategic assignments need to be managed differently. While each business unit needs to tailor its strategy to fit its strategic assignment, the corporate center will need to manage the various categories of business units differently. Especially the businesses with a turnaround and divest assignment might require a separate approach and/or team.

- The Strategic Assignment Matrix is a complementary portfolio analysis tool. Most other portfolio analysis tools, such as the BCG Matrix and GE Business Screen, map each unit’s future potential, but don’t suggest a strategic assignment. The Strategic Assignment Matrix is a complementary tool that can best be used after a first portfolio analysis to agree on the strategic assignment that each unit will be given.

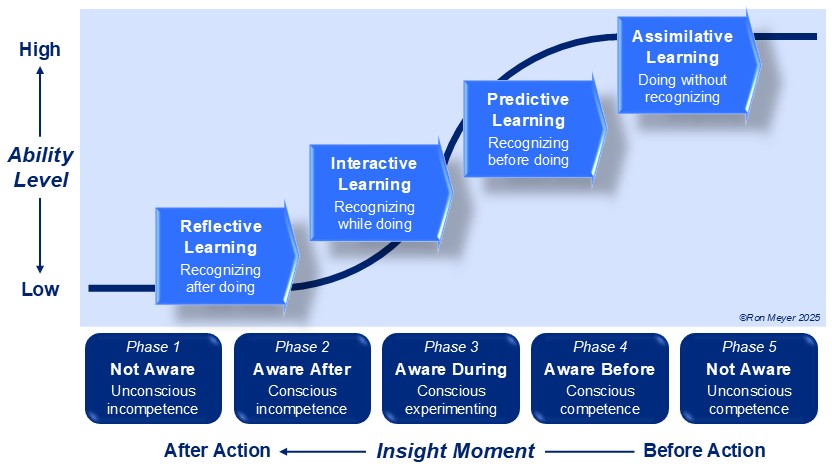

Key Definitions

An ability is the potential to act competently – a skill to do something well. Some abilities take place in people’s heads, such as thinking and feeling, but many more express themselves in behaviors, such as speaking, writing, listening, standing, moving and looking.

Learning is the process of improving one’s knowledge and/or abilities. Some learning can take place quickly, but learning abilities usually requires practice, as uncomfortable new behaviors need to become comfortable routines. This is particularly true if the new ability clashes with ingrained habits and/or deeply held beliefs, or if someone has limited innate talent in that area.

Conceptual Model

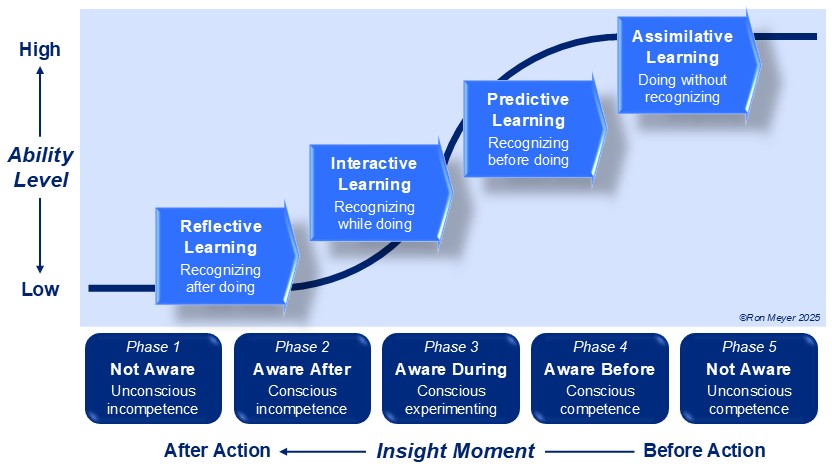

The New Learning Curve model presents an overview of how people acquire a new ability. It suggests they typically go through five phases, from not knowing they don’t have an ability (phase 1) to mastery (phase 5), requiring four different types of learning to move from each phase to the next. It is important to note that the horizontal axis doesn’t depict regular time, but rather the moment at which the learning takes place. It runs from learning by reflecting on the results after trying, to recognizing what works while doing, to gaining insight even before acting. In this sense, the time axis is reversed. The model’s message is not only that mastery takes time, but that people need to change their type of learning along the way. The model’s name is a nod to the “old” learning curve, that posits that ability simply increases with experience.

Key Elements

The four sequential types of learning needed to master a new ability are the following:

- From Phase 1 to Phase 2: Reflective Learning. Most people know they can’t fly a plane, but few people realize they lack competence in giving feedback or chairing meetings. Many abilities seem common sense, such as speaking or listening, so people aren’t conscious of how limited their abilities are. Therefore, the first step in learning is to become aware of what ‘good’ looks like and then to reflect on one’s own shortcomings. By recognizing the gap between what could be and how they just acted, people become cognitively and emotionally ready to change. They aren’t more able yet, but the learning has started.

- From Phase 2 to Phase 3: Interactive Learning. The second type of learning is where people experiment with new behaviors. Interactive learning is simply learning-by-doing, improving one’s ability by practice. The challenge in moving to phase 3 is that people must recognize the situation while it is happening and adapt their behavior on the fly. It is so easy to fall back on old routines and afterwards have to conclude that you fell into the same old traps. Therefore, it helps to practice new abilities off the field first (training), preferably with a coach who can give pointers along the way. And then it’s practice, practice, practice.

- From Phase 3 to Phase 4: Predictive Learning. The third type of learning needed on the road to mastery is where people start to anticipate what will happen in a certain situation and then adapt their behavior ahead of time. Predictive learning is about foreseeing what is required before moving into action. The challenge of reaching phase four is that people must recognize a situation upfront, while their mental map has been shaped to interpret the circumstances in the old way. Therefore, it helps to consciously assess the situation and review various angles, before deciding what to do.

- From Phase 4 to Phase 5: Assimilative Learning. The fourth type of learning is where an ability becomes a new routine. Assimilative learning is the process of automating a particular skill to such an extent that it can be performed without conscious effort or even thought. True mastery of an ability makes it look easy, leading some to believe that a person must have an innate talent, while in reality every ability must be learned through hard work. Moving to phase five doesn’t necessarily make a person more competent, but it does require less effort, freeing up mental space to develop other abilities as well.

Key Insights

- Learning is the only way to develop abilities. No one is born with an ability, only with talents. A talent is a predisposition to learn something more quickly and/or reach a higher level of competence, but it can only become an ability by going through a learning process.

- Learning is frustrated by routines and beliefs. Developing an ability requires learning ‘how to do’ (skills/routines) often rooted in an understanding of ‘what to do’ (assumptions/ beliefs). But existing routines and beliefs are often deeply ingrained in a person’s system, making it difficult to learn new ones, especially where they are conflicting.

- Learning moves through five phases. When people learn a new ability, they typically go through five phases. They start not aware they are unable (phase 1), then become aware of this (phase 2), followed by being aware they are learning (phase 3), after which they are aware they are able (phase 4), and finally taking their ability for granted (phase 5).

- Learning comes in four types. Each phase transition on the learning curve requires a different type of learning. First comes reflective learning (“where am I unable?”), then interactive learning (“practice, practice, practice”), then predictive learning (“knowing when to do what”) and finally assimilative learning (“internalizing it as standard repertoire”).

- Learning can be facilitated and sped up. People learn all the time, but not always consciously. The new learning curve model helps people – and their coaches – to realize where they are on the learning curve for each ability, so they can more deliberately determine which type of learning they require to move to the next level of ability.

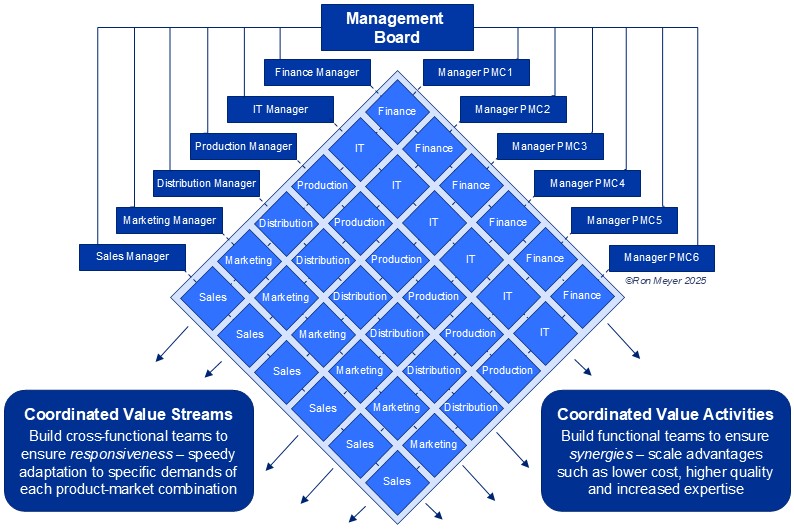

77. Organizational Diamond

Key Definitions

An organization is a group of people striving towards a shared goal over a prolonged period of time, who have divided the necessary work between them (differentiation), while coordinating their efforts (integration) to achieve the intended result together (Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967).

An organizational structure is the design used to divide work activities between units and individuals (task allocation), while ensuring that, where necessary, these activities are aligned (task coordination) and they are performed efficiently and effectively (task supervision).

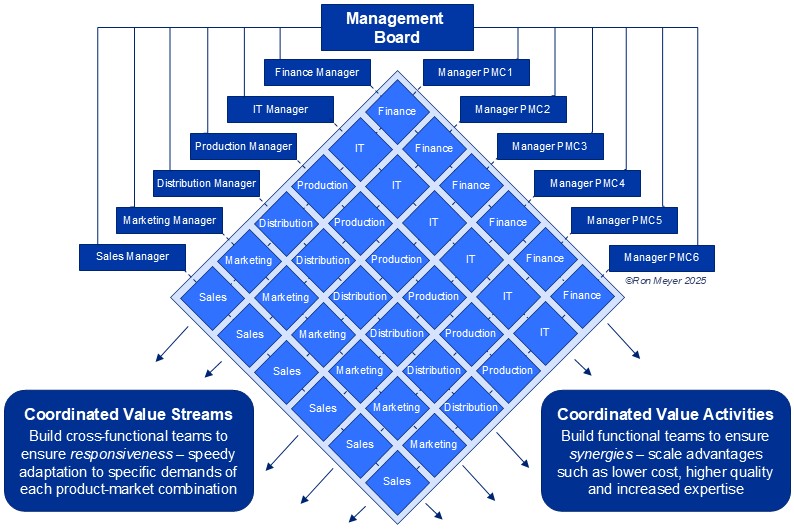

Conceptual Model

The Organizational Diamond framework offers a simple key for designing even complex organizations. It is based on the premise that when structuring an organization designers need to balance, on the one hand, the advantages of keeping similar value activities together in functional teams (diagonally on the left), with on the other hand the advantages of keeping complementary value activities together in cross-functional value stream teams (diagonally on the right). In other words, every organizational design is fundamentally a balancing act between achieving internal synergies and external responsiveness. When deciding on the most effective structure, this trade-off needs to be considered at various levels of aggregation.

Key Elements

The two fundamental design principles are the following:

- Coordinate Value Activities to Achieve Synergies. Keeping similar value-adding activities together in one person or department can create scale advantages, such as lower cost, higher quality and increased expertise. This is the internal functional team logic, usually leading to functional managers at the head of departments (see top left). However, these synergies are only viable if the activities are (made) similar enough.

- Coordinate Value Streams to Achieve Responsiveness. Keeping complementary value-adding activities together in one person or department can create responsiveness advantages, such as market adaptability and customer-centricity. This is the external cross-functional team logic that is particularly important if markets are very different. This leads to having business unit, product line and/or regional managers as department heads.

The framework then suggests the following organizational design process:

- Evaluate Building Blocks Bottom-Up:

- Map out all main value-adding activities. Determine a detailed picture of all of the work that needs to be done (the light blue examples in the diagram, but more detailed).

- Assess the responsiveness advantages. Determine how different each product-market combination (PMC) is and what the benefits of tailoring to each would be.

- Assess the synergy advantages. Determine how similar various activities are and how large the scale benefits could be.

- Structure Building Blocks Top-Down:

- Design main structure. Determine whether the main structure will be function-based or market-based (by business, region or customer group). At the next level do the same.

- Design secondary structure. Determine where the “fixed line” coordination needs to be supported by “dotted line” coordination. Do this at every level, from the top down.

- Slot people into the structure. Determine which person should be on which team, to carry out which activities. Recruit/replace people to fit with the activities.

Key Insights

- Organizational design is about value creation. Organizations are groups of people, but their design shouldn’t be based on the people, but on the value they are intended to create. Organizations should be fit for purpose, so structuring them starts with understanding which value-adding activities need to be carried out and how these can be performed as efficiently and effectively as possible. So, first structure the activities, then add the people.

- Organizational design balances internal and external logics. All the value-adding activities can be coordinated in two ways: similar activities can be clustered to create internally oriented synergies, while complementary activities can be clustered to achieve externally oriented responsiveness. These opposite possibilities need to be balanced.

- Organizational design should always start with business design. Whether the diamond should tip to the right, emphasizing functional synergies, or tip to the left, focusing on market responsiveness, depends on the chosen business strategy. Structure follows strategy (Chandler, 1962). The business model determines which activities to coordinate.

- Organizational design should be bottom-up and then top-down. Structuring should start with a bottom-up understanding of all the required value-adding activities and the potential for synergy and responsiveness advantages. Only then can clustering choices be made, starting from the top down, with a first level of structuring, followed by multiple next levels, each time using the same internal-external advantage trade-off.

- Organizational design balanced fixed line and dotted line. While the main structure determines the formal divisions and reporting lines, there is usually still room to coordinate between activities across units/departments using a variety of “dotted line” integration mechanisms. See the 11C Synergy Model (#8) and Customer-Centricity Model (#51).

Key Definitions

Strategy is the course of action being followed and is usually shaped by three types of aims: a long-term aim called a strategic vision (also called a horizon 3 goal, typically 5-10 years into the future), some mid-term aims called strategic objectives (horizon 2 goals, typically 2-3 years out) and multiple short-term aims called strategic targets (horizon 1 goals, 6-12 months out).

Ideally, when setting an intended strategy, people should think future-back, first formulating their vision and objectives as a big picture and then filling in the targets that need to be reached in the shorter term, along with a detailed plan of action. To know what to do, such a plan should be SMART – Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic and Time-bound.

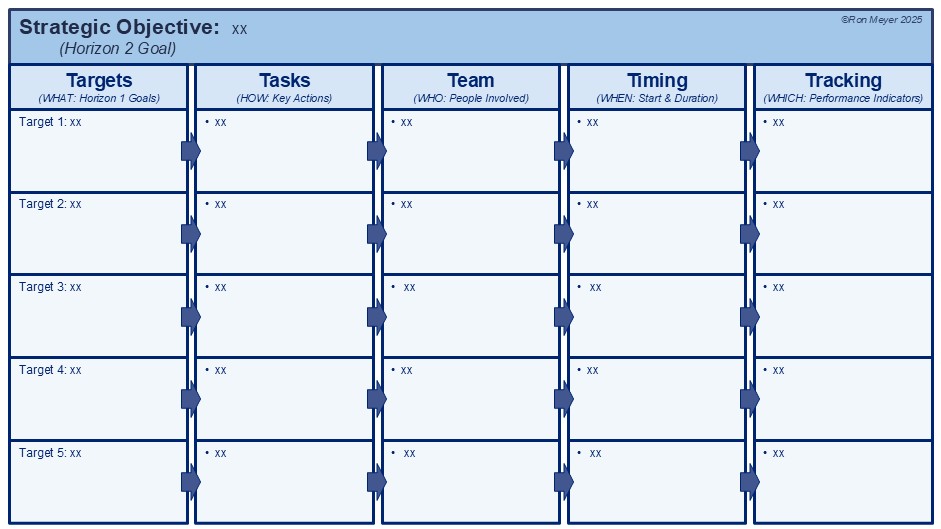

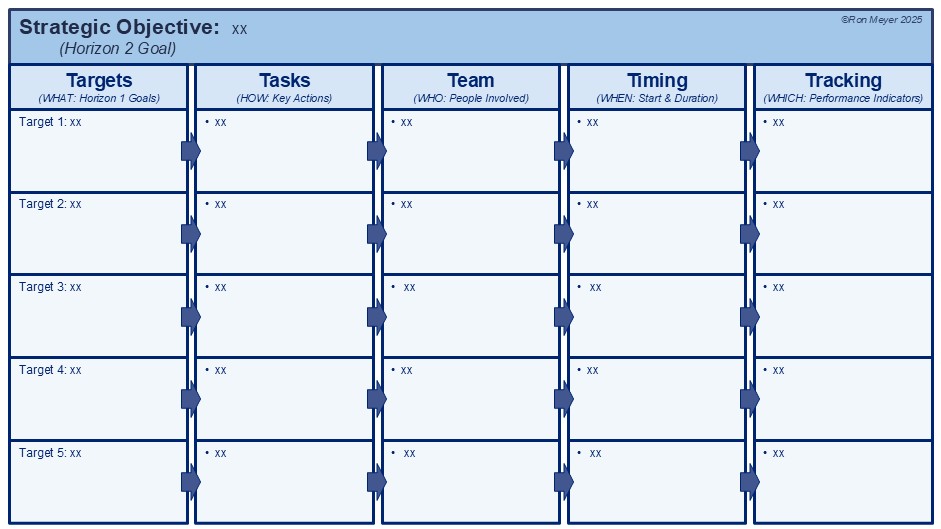

Conceptual Model

The 5T SMART Plan template offers a one-page framework for detailing each strategic objective in an organization’s big picture strategy. It asks the user to identify at most five strategic targets that need to be realized for each strategic objective, followed by the required key actions, people involved and timing of each action and some measure by which progress towards the target can be tracked. As such, the 5T SMART Plan is more detailed and tangible than the widely used OGSM (Objectives-Goals-Strategies-Measures) framework, while it also avoids the confusion of using the word “strategies” incorrectly.

Key Elements

The six categories of the template are the following:

- Strategic Objective. Based on the overarching strategic vision (see Meyer’s Management Models #56), every strategy should identify a limited number of strategic objectives to be pursued in the coming 2-3 years. These core pillars of an organization’s strategy are also called strategic guidelines or must-win battles. For each, a template should be completed.

- Targets. Just as the vision needs to be broken down into shorter-term objectives, each objective needs to be broken down into even shorter-term targets – typically goals to be reached in the coming 6-12 months. The template only provides room for a maximum of five targets, to force the setting of priorities, but in practice extra targets can be added.

- Tasks. The targets in turn need to be broken down into tangible actions that need to be taken in the short run. Again, the limited room in the template is intended to force the user to prioritize the key actions and to avoid drawing up an overly detailed blueprint. Of course, in a follow-up template, an even more fine-grained planning can be created if necessary.

- Team. For each of the tasks it needs to be determined which people will be involved and in what type of capacity – lead, contributor or supervisor. By completing this part of the template, it will become clear where people bottlenecks show up and teams need to be reshuffled, new people need to be recruited, or tasks need to be delayed to a later moment.

- Timing. Based on the assessment of the required task and team, it can be determined when each activity should start and how long each should take. Again, while the logic of the template flows from left to right, sometimes timing-issues will force a few iterations, going back to adjust the team or the tasks to the demands of timing.

- Tracking. Finally, to complete the plan-do-check-act cycle, it is important to have some measures of how well the “doing” is going. Therefore, for each task some indicator needs to be identified for tracking execution (progress check), while another indicator might be required to review whether the intended target is being realized (result check).

Key Insights

- Strategy needs to be operationalized. Most strategy formulation exercises result in a big picture strategy document, focusing on the broad sweep of the strategic direction, including a strategic vision and some strategic objectives. The lurking danger is that this high-level strategy is not made SMART enough for people in the organization to know what to do.

- Strategy needs a tree of goals. An internally consistent strategy should be designed from the future back like a tree diagram of goals. A strategy should start with one long-term goal, the strategic vision, as the tree trunk, that then branches out into a few mid-term goals, the strategic objectives. These in turn should each branch out into several short-term goals, the strategic targets, that then branch out into various tasks. The closer one gets to the current moment, the more numerous and detailed all the branches will be.

- Strategic planning requires determining five Ts. Detailing these branches is a large part of the strategic planning process. For each of the main branches (strategic objectives) a 5T template should be completed, specifying the sub-branches (targets) and sub-sub-branches (tasks), followed by determining who should be involved (team), when activities should be carried out (timing) and which way progress should be measured (tracking).

- Strategic planning requires iterations. While the logic of the 5T template is from left to right, in practice there will be many moments at which various branches of the tree will be at odds with each other, either by pushing in conflicting directions or more often by making use of the same scarce resources. Therefore, the planning process will often go through multiple iterations to achieve alignment between the parts.

- It’s time to retire OGSM. For many years people have used the OGSM framework, defining Objectives, Goals, Strategies and Measures, leaving out the key factors of team and timing, and confusingly calling tasks “strategies”. It’s time for an update.

75. Conversation Elevator

Key Definitions

While some people can work on their own, managers need to spend most of their time in conversation with others – engaging in two-way communication with the intention of achieving some result, such as gaining a better understanding, making a decision, or moving into action.

Conversations involve the simple act of verbally interacting with each other, sometimes on a one-to-one basis, while at other moments in larger group settings. But while interacting is commonplace and easy, interacting effectively is rarer and more difficult. It requires both sides to talk to each other in a particular way, in other words, to use a specific conversation type.

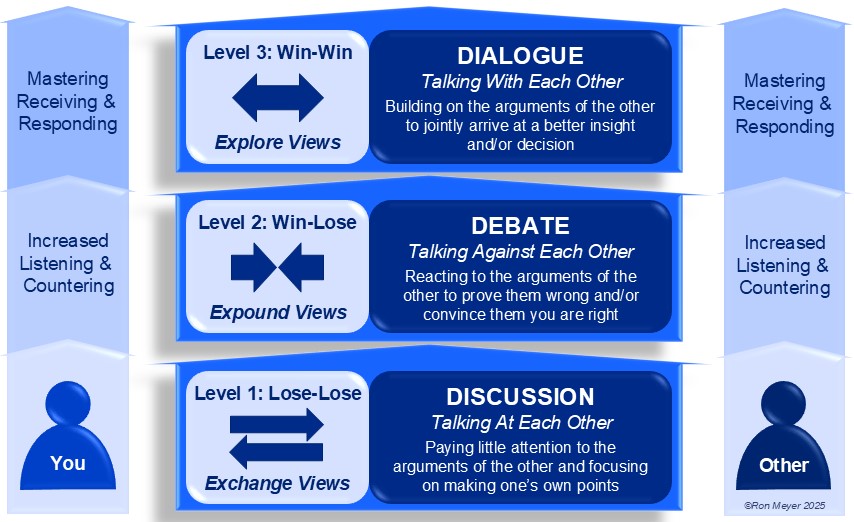

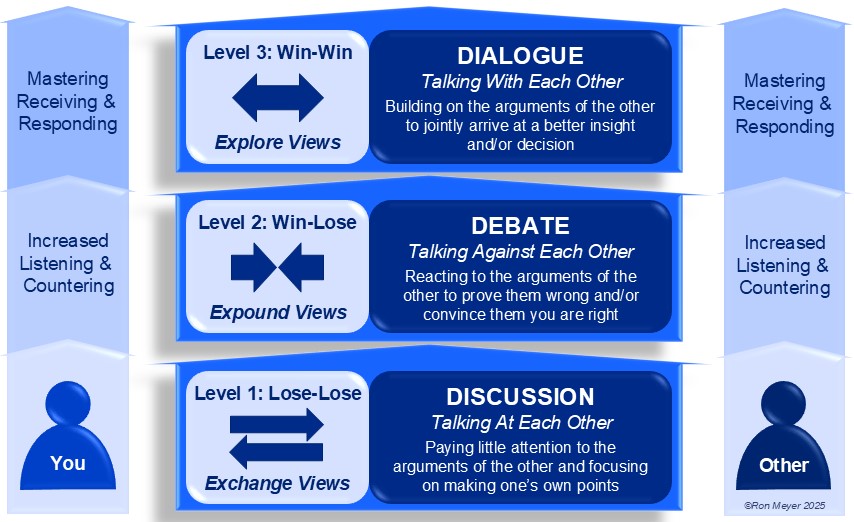

Conceptual Model

The Conversation Elevator model distinguishes three conversation types, that from bottom to top progressively lift the interaction to a higher level of effectiveness. The model suggests that if people are not intentional about how they engage in conversation, they will get stuck at the ground floor; in discussion, exchanging views, talking at each other, with little impact on either’s opinion. To move one level up, to a debate type conversation, they need to start listening and talking against the other, with the intention of expounding their views and convincing the other. To elevate the conversation to the level of dialogue, at which people talk with each other, exploring each other’s views, requires the mental shift of wanting to truly understand the other’s perspective, in order to build on it. This is usually the most effective conversation type.

Key Elements

The three types of conversations are the following:

- Discussion: Exchanging Views. A discussion is a type of conversation in which each speaker is more interested in being heard than in hearing – each broadcasts their own views, with limited attention being paid to arguments put forward by others. In the worst case, it is hardly two-way communication, but various people engaged in one-way communication simultaneously. Typically, people in a discussion will be caught up in their own thought processes, which they need to make consistent and justify, with little cognitive bandwidth to make sense of someone else’s views. Therefore, they will keep on repeating their own truth and only respond to people’s points if they neatly fit in their own worldview.

- Debate: Expounding Views. A debate is a type of conversation in which at least one side is intent on “winning” – proving they are right and the other is wrong. While in a discussion both sides are too busy with their own thought processes to hear what the other means, in a debate people do actually listen to each other, but to find weaknesses in the other’s arguments, so they can open a new avenue of attack. The listening is not open-minded and constructive, but partisan and offensive, giving the verbal boxer more opportunities to land a counter punch. Still, a debate is more effective than a discussion in highlighting the relative strengths and weaknesses of various points of views. So, debates can be useful.

- Dialogue: Exploring Views. A dialogue is a type of conversation in which both sides build on each other’s ideas to reach more insight – they use their different perspectives and joint brainpower to reach conclusions they won’t have been able to achieve separately. This requires all participants to receive the others’ arguments without immediate judgement and with the intention of trying to understand their point of view. Only once this new information is digested, can a tailored response be formulated that tries to bring the argument further. If the goal of both sides is to explore issues together and/or reach more considered decisions, then this type of conversation tends to be the most effective.

Key Insights

- Conversation is a key management tool. Talking might be managers’ most widely used tool for getting things done. This talking is sometimes one-directional, as when managers give a presentation, tell people what to do, or give a compliment. But more often, it is two-way communication, in which people talk about issues and argue about potential ways forward. This verbal interaction between two or more people is called conversation.

- Conversation comes in three types. There are three types of conversations. A discussion is where parties exchange views, without much reaction to the others’ opinions. This adds little value and is therefore classified as lose-lose. In a debate each party expounds their views, trying to prove they’re right and the others wrong, making it a win-lose affair. In a dialogue all parties explore each other’s views, with the intention of gaining deeper insight, making it a win-win type of conversation.

- Each conversation type has a different view of the other. Someone in discussion-mode sees the other as audience that needs to be told. Someone in debate-mode sees the other as opponent that needs to be convinced. Someone in dialogue-mode sees the other as sparring partner who can help to figure things out.

- Conversations can be elevated to a higher level. When people don’t think about their conversation intentions and the role of their counterparts, they quickly get stranded in discussion. They can elevate a conversation to reach a specific goal, such as getting their way (debate) or gaining more understanding (dialogue) but need to do this consciously.

- Effective conversation requires better listening. Moving to a higher conversation level starts with trying to understand the other, reacting to their points, and then subsequently asking them to listen and respond to you, instead of allowing them to repeat their initial position. This process is also described in the Disciplined Dialogue model (#29).

Key Definitions

Innovation is not an event but a process, taking months or years to bring a novel idea to a tangible new product, procedure or business. As organizations know that not all innovation ideas will come to fruition, they typically pursue various initiatives at the same time. Together, the portfolio of innovation initiatives at various stages of development is called the innovation pipeline (see Meyer’s Model #44, the 5I Innovation Pipeline).

An innovation pipeline can be ad hoc and informal but is often organized and run in a more structured way. Innovation management is the set of formalized organizational conditions intended to optimize the output of an organization’s innovation pipeline.

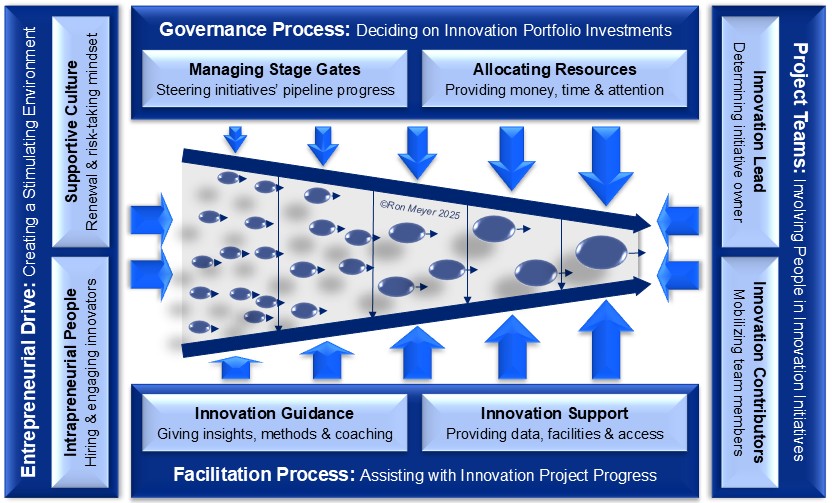

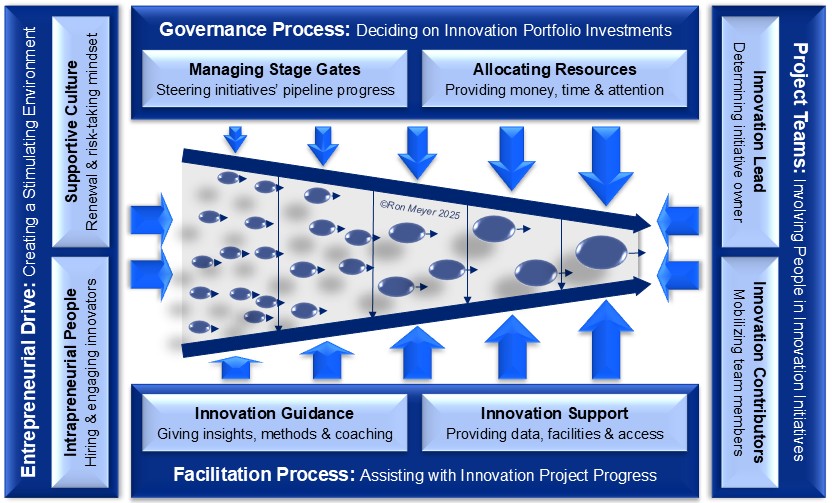

Conceptual Model

The Innovation Arena model identifies the four sets of innovation management interventions that can be used to improve the output of an organization’s innovation process. At the center of the arena is where the innovation game itself is played, represented here by the earlier discussed 5I model. Surrounding this “innovation field” is a frame made up of the four building blocks of innovation management, each consisting of two parts. By wisely using these eight influencing factors, organizations can improve their success on the innovation pitch.

Key Elements

The innovation arena’s frame consists of the following elements:

- Governance Process. Throughout the innovation process, decisions need to be made about investments and whether to let initiatives proceed. This responsibility can be taken by the Board of Management or given to a separate Innovation Board. They need to:

- Manage Stage Gates. Determine which criteria need to be met to proceed, monitor how each initiative is doing and decide when to support or kill projects in the pipeline.

- Allocate Resources. Determine which resources are required for each initiative and select which set of initiatives is the optimal investment portfolio.

- Facilitation Process. Next to being judged, initiatives also need to be helped along. This assistance can be sought in the broader organization, or an innovation manager/office can be instituted to provide more structured facilitation. This help typically includes:

- Innovation Guidance. Giving advice and feedback, providing methodologies and tools, and aiding the building of strong innovation project teams.

- Innovation Support. Providing access to the necessary data, facilities, subsidies, services and internal and external partners.

- Entrepreneurial Drive. While governance and facilitation can guide the innovation process, there also needs to be a spirit to innovate – a climate that engenders innovative initiatives. Top management, together with an innovation manager, need to work on:

- Intrapreneurial People. Bringing in innovative people from outside, while stimulating insiders, getting them to take initiatives and recognizing them for their efforts.

- Supportive Culture. Encouraging a curious, creative and risk-taking mindset, legitimizing failures and celebrating successes, all while leading by example.

- Project Teams. Throughout the pipeline, innovation managers shouldn’t innovate, but should guide the innovation process, involving the right people for each of the initiatives. Top management, together with the innovation manager, need to mobilize:

- Innovation Leads. Identifying the best possible candidates to drive each initiative and getting them to take ownership and responsibility for achieving results.

- Innovation Contributors. Identifying the required supporting team members, as well as project sponsors and other supportive (potential) stakeholders.

Key Insights

- Innovation can be managed. The flow of innovations in an organization can happen haphazardly, or can be structured into an organized innovation pipeline, that can be purposely managed to optimize the outputs given the resource investments available.

- Innovation management is the arena around the innovation pitch. There are four ways to optimize how the innovation game is played. Together, these four categories of innovation management interventions form the four sides of the innovation arena.

- Innovation management has two process sides. The innovation arena has two process sides, that influence how initiatives flow through the pipeline. The governance process comes from above and decides on investments and next steps (growing arrow sizes symbolize growing involvement). The facilitation process comes from below and assists in moving initiatives forward (the stable arrow size symbolizes consistent support throughout).

- Innovation management has two people sides. The innovation arena also has two people sides, that influence how engaged individuals feel throughout the process. From the outset the entrepreneurial drive felt by people in the organization will shape their eagerness to participate in innovation initiatives. As these initiatives progress, people will be invited to join project teams, giving them the opportunity to contribute to innovation.

- Innovation management requires innovation managers. All these activities require dedicated attention. Therefore, an Innovation Board is often required for the governance and an Innovation Manager for the facilitation, while tackling the other activities together.

Key Definitions

A business unit is a part of an organization that can potentially be run independently, as a separate business. It generally needs to perform front-office activities that are market-facing (such as marketing and sales), mid-office activities that are product-related (such as production and logistics) and back-office activities that are support-oriented (such as HR and finance).

Leaving business units largely independent allows them to be responsive to their specific market demands. But they can also be partially integrated to realize synergies, such as scale economies and market power (see model 64, Corporate Synergy Typology). Therefore, balancing the level of integration is called the paradox of responsiveness and synergy.

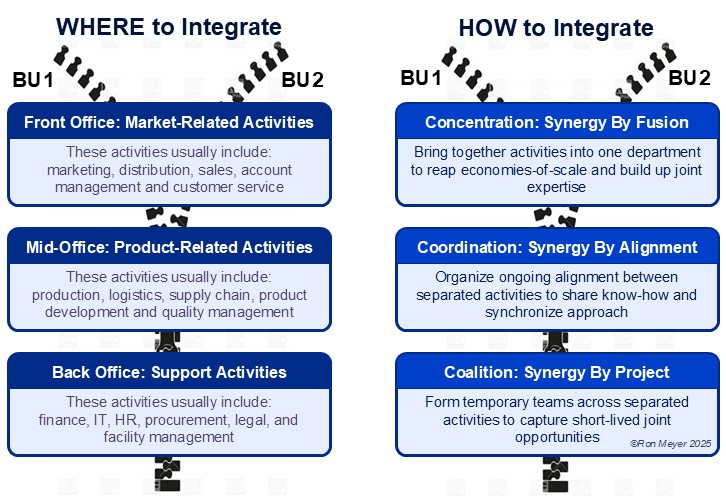

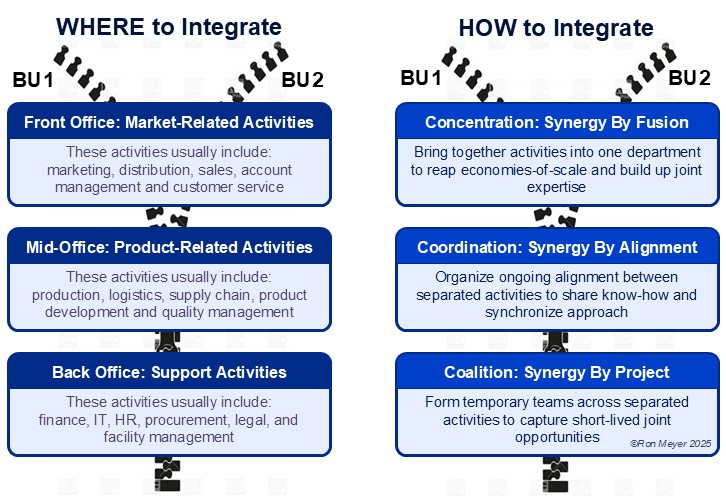

Conceptual Model

The Integration Zippers is a model for thinking about various organizational possibilities between the extremes of total separation and full integration of business units. Using the metaphor of a zipper, the model suggests that business units should be integrated starting from “the bottom” up, at each point considering whether further zipping make strategic sense. The left-hand zipper deals with which activities to integrate, proposing that back-office, then mid-office and finally front-office is the preferable order. The right-hand zipper deals with the manner of integration, advising to first consider only using projects, then to weigh whether ongoing alignment would be better, and then ultimately to even contemplate using full fusion.

Key Elements

The two Integration Zippers consist of the following elements:

- WHERE of Integration. Not all activities are as easy to integrate, particularly because integration leads to less responsiveness – less ability to differentiate the activity to fit with the specific demands of the market, and less agility to rapidly adapt to market changes. Generally, the further an activity is from the market, the less responsiveness is required, making a potential synergy more attractive. Therefore, the preferred integration order is:

- First Back-Office. Support activities such as finance, IT, procurement, research, HR, legal and facility management tend to be less business-specific and therefore easier to share across business units, so they should be considered first.

- Then Mid-Office. These are all activities directly contributing to the creation of the product or service, from product development to supply chain, production and delivery, and they can be shared if the creation process is relatively similar.

- Finally Front-Office. These are all activities that directly interact with customers and other market actors, including marketing, distribution, sales, and customer service, and can only be shared if the markets are similar. These should be considered last.

- HOW of Integration. Integration is not a binary choice between “yes” and “no”, but a choice between different levels, from “light” to “tight”, by varying the type of integration mechanism employed – the organizational set-up used to realize the intended synergy. Generally, the tighter the mechanism, the higher the synergy, but also the lower the responsiveness. Therefore, it’s best to start by considering light integration and then evaluate tighter forms:

- First Coalition: Synergy by Project. The lightest integration mechanism is to form temporary teams around specific projects, to allow knowledge to be transferred, best practices to be shared or certain customers to be jointly served, all for a limited time.

- Then Coordination: Synergy by Alignment. If more permanent collaboration is required, a tighter integration mechanism is to formalize ongoing alignment, to ensure that activities on both sides strengthen to each other, while still staying separate.

- Finally Concentration: Synergy by Fusion. If structural coordination is insufficient to achieve the intended synergy, then the tightest integration mechanism will be needed, which is the full fusion of both units’ activities into a merged whole.

Key Insights

- Integration is bringing together business units. When two or more business units give up some of their independence and to work together, this is called integration. Sacrificing their autonomy generally reduces their ability to be responsive to the specific demands of their market but increases synergies. Determining the optimal level of integration depends on finding the preferred balance between responsiveness and synergy.

- Integration has a “where-side” and a “how-side”. Business units need to assess which activities to integrate (the “where” of integration) and in what way to integrate these activities (the “how” of integration).

- Integration can be across three types of activities. “Where to integrate” can be divided into three general categories, based on how far away they are from market demands: Back-office activities (support functions that are often less business-specific), mid-office activities (product-related functions that are more business-specific) and front-office activities (highly business-specific market-facing ones).

- Integration can be at three levels of intensity. “How to integrate” distinguishes three different integration mechanisms: Using coalitions (temporary projects), coordination (continuous alignment) or concentration (permanent fusion).

- Integration should follow the zipper approach. Both “where” and “how” to integrate should be answered by zipping from the bottom up, gradually and thoughtfully considering how far to go to achieve the optimal balance between responsiveness and synergy.

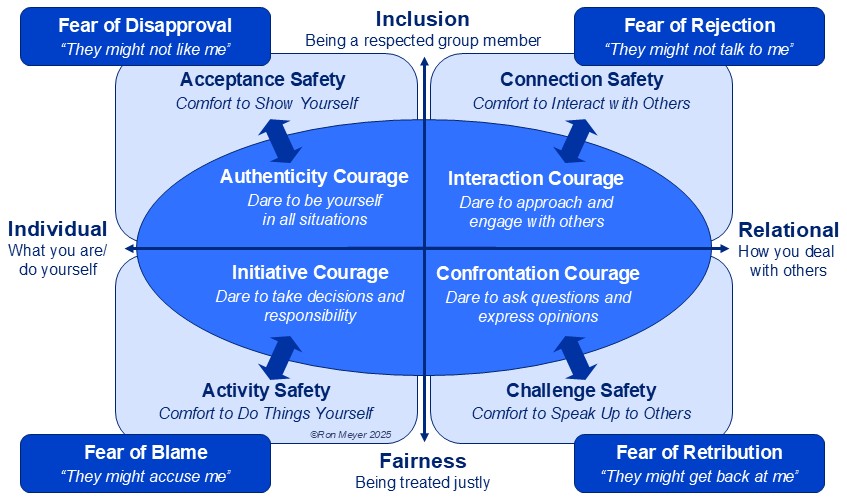

72. Courageous Core Model

Key Definitions

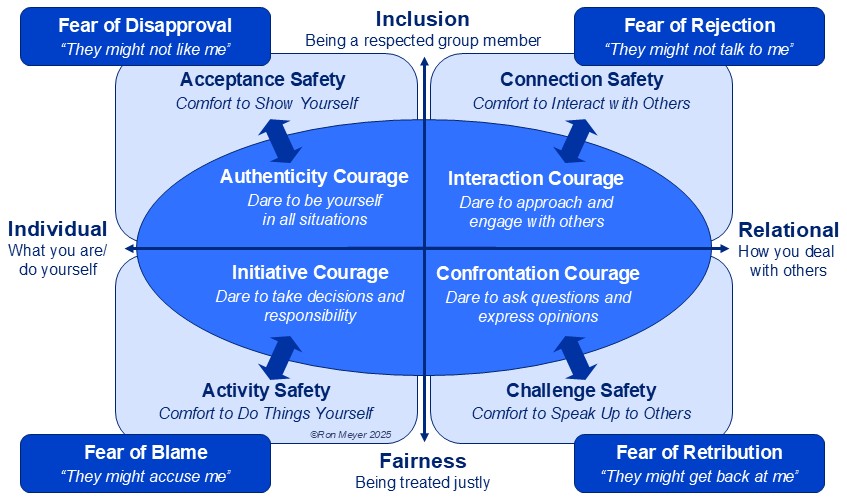

Courage, or bravery, is the quality of overcoming fear – it is the psychological strength to act despite experiencing a feeling of dread. People are courageous when they sense that they face an unsafe situation and still maintain their ability to function.

Soldiers, firefighters and police officers must sometimes deal with a lack of physical safety, but everyone must regularly deal with a lack of psychological safety. People can feel psychologically unsafe if they fear negative social reactions, such as disapproval, rejection, blame and retribution.

Conceptual Model

The Courageous Core Model builds on the Psychological Safety Compass (Meyer’s Management Models #40), that outlined four common fears (below in dark blue) and the four related types of psychological safety that leaders should strive to provide to the people around them (in light blue). But while the Psychological Safety Compass highlighted the role of the leader in creating a safe environment, the Courageous Core Model emphasizes the responsibility of every individual to act bravely. The model suggests that no environment can be made entirely safe, so people need to build up a courageous core to dare to function despite their fears. The less safety on offer externally, the more courage that will be required internally.

Key Elements

The four types of courage required are the following:

- Authenticity Courage: Dealing with the Fear of Disapproval. Everyone would like to be accepted for who they truly are, without the need to live up to other people’s expectations. However, in many circumstances, behavioral norms are strict, people are judgmental, and you will be pressured to conform to preconceived notions of how things should be. But instead of caving in to this looming social disapproval, you can exhibit authenticity courage, by staying close to your genuine self. This can include looking and sounding different, coming from a different background, and having different thoughts, opinions and feelings.

- Interaction Courage: Dealing with the Fear of Rejection. Even introverts like it when it is easy to talk to other people and everyone feels at ease in each other’s company. However, in many situations, social interactions are far from smooth, as status differences and group affiliations come into play, giving you a signal that you are not part of the in-crowd. But instead of avoiding people because of the fear of being rejected, you can exhibit interaction courage, by trying to connect, nevertheless. This can range from simply striking up a conversation, all the way to asking to be included in others’ circle or club.

- Initiative Courage: Dealing with the Fear of Blame. To get things done, people need to make decisions and take actions, but there is always a danger that mistakes will be made and/or that things will go wrong. In many situations, the first response to a failure is not to search for a solution, but to seek out the guilty, so taking on responsibilities can be rather risky. In the same way, making tough choices can be dangerous, as dissatisfied stakeholders will vent their anger at the decision-maker. Yet, instead of shying away from taking action, you often need to show initiative courage and risk taking some of the blame.

- Confrontation Courage: Dealing with the Fear of Retribution. It is in the clash of ideas and perspectives that new insights develop, and creative solutions are formulated. So, you would expect that challenging people’s views and asking tough questions would be seen as valuable aspects of group interaction. However, in many circumstances, such diversity of opinion is seen as disruptive and disrespectful, so needs to be suppressed. But instead of faking consensus to avoid the threat of retribution, you can exhibit confrontation courage, by posing uncomfortable questions and suggesting unpopular alternatives.

Key Insights

- Courage is about overcoming fear. Being courageous doesn’t mean you’re not scared, but rather that you have the willpower to act despite being scared. Courage is the quality that makes you choose fight over flight when confronted with a dangerous situation.

- Courage is required when safety is lacking. Without danger, courage is not required. But the more unsafe a situation, the more courage is required to act. Situations can lack physical safety, but more often people need to overcome a lack of psychological safety.

- Courage is about overcoming four types of fear. People can have two types of social inclusion worries, namely the fear of not being accepted for who they are (fear of disapproval) and not being welcomed as social counterpart (fear of rejection). They can also have two types of fairness worries, namely the fear of being unjustly condemned for actions they have taken (fear of blame) and unjustly retaliated against for speaking up (fear of retribution).

- Courage also comes in four types. Fear of disapproval can be countered by daring to be yourself (authenticity courage), fear of rejection by daring to engage with others (interaction courage), fear of blame by daring to take decisions and responsibility (initiative courage) and fear of retribution by daring to express opinions (confrontation courage).

- Courage comes from the inside, safety from the outside. Leaders can try to create a safe environment, but people need to strengthen their inner core of courage themselves. Resilience to danger starts with taking responsibility for building one’s own brave heart.

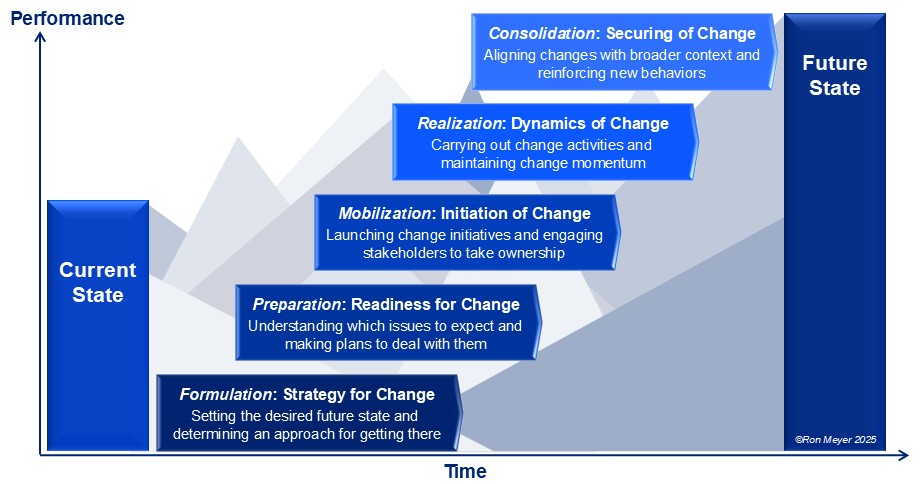

71. Five Phases of Change

Key Definitions

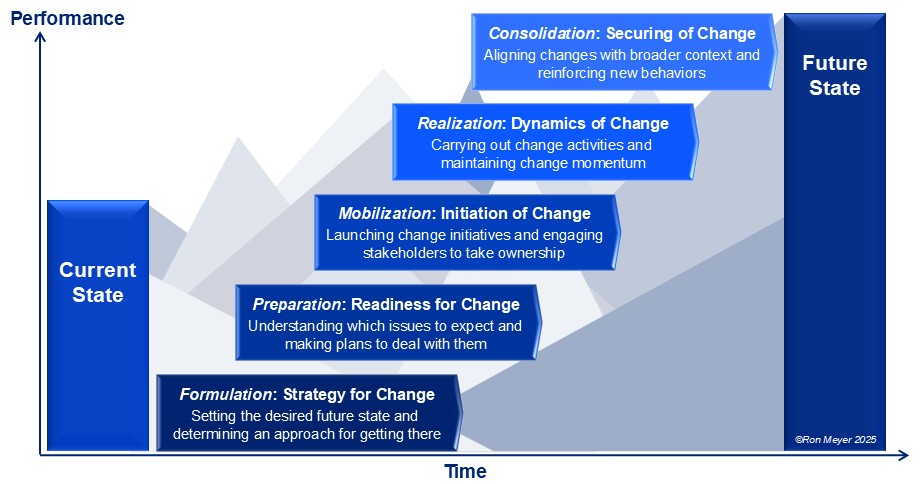

As outlined in the Mind the Gap Model (Meyer’s Management Models #1), organizational change is the process of transitioning an organization (or parts thereof) from a current state to an intended future state. Some organizational changes are incremental (small and gradual), others transformational (large and rapid), while most are somewhere in between.

Few organizational changes take place in a fixed number of orderly steps. Most processes are like rivers – messy streams of activities, occasionally speeding up and slowing down, flowing forward, but also curling back. Therefore, it is better to speak of generic phases or stages in a change journey, instead of thinking in terms of distinct change steps.

Conceptual Model

The Five Phases of Change model outlines the five general stages recognizable in any change journey, as the organization moves from the current state through mountainous ups and downs to the desired future state. The five phases overlap along the time-axis, visually conveying the message that a change journey doesn’t take place in neat sequential steps, but that change activities belonging to different phases can sometimes take place simultaneously and that the journey can occasionally even loop back to an earlier phase. The model is intended to be a simple map to plot complex change processes and to help recognize what type of interventions might be required given the phase that the organizational change is in.

Key Elements

The five generic phases of organizational change are the following:

- Formulation: Strategy for Change. The first phase of any change journey is to determine where the voyage is going (change destination), who the voyagers will be (change stakeholders) and how the voyage will take place (change approach). The key challenge is to avoid the ambiguity hazard – the danger of not making clear choices. For a change journey to be successful, the definition of the future state must give a concrete sense of direction, while a viable path for getting there must be set. “We’ll see” is not a strategy.

- Preparation: Readiness for Change. The second phase is to ensure that the organization is ready to embark upon the selected path, by taking away barriers to change (securing change ability) and resistance to change (securing change willingness). The key challenge is to avoid the contracting hazard – the danger of accepting a change strategy for which the organization is not ready. If the organization can’t be made willing and able to follow the selected change path, it might be necessary to loop back and reformulate the strategy.

- Mobilization: Initiation of Change. The third phase is to get the ball rolling, by creating a virtuous cycle of engaging sufficient stakeholders to realize visible changes, thereby building confidence and commitment, that in turn will convince more stakeholders to jump on the bandwagon. The key challenge is to avoid the momentum hazard – the danger of not reaching take-off speed. If too many stakeholders are reluctant to commit themselves to the change journey, tangible results will be lacking, triggering a vicious downward spiral.

- Realization: Dynamics of Change. The fourth phase encompasses all of the actual work of carrying out the required changes. In this, often long, leg of the change journey, the ball needs to keep rolling and a constant stream of activities needs to be completed, while results need to be achieved. The key challenge is to avoid the setback hazard – the danger of suffering a reversal of fortunes, leading people to question the feasibility of the changes. To be successful, organizations need to overcome such blows and carry on.

- Consolidation: Securing of Change. The fifth phase is concerned with making sure that all of the changes are completed, even if resources are running low, people are getting tired and new change projects present themselves as even more urgent. The key challenge is to avoid the anchoring hazard – the danger of not securing all of the realized changes, with people backsliding into old systems and behaviors. Successfully finishing the change journey requires the diligent discipline of tightening up the last nuts and bolts.

Key Insights

- Change journeys are all different. Organizational changes come in many shapes and sizes. They can be broad or narrow in scope (breadth), large or small in scale (height), and rapid or slow in speed (length). Moreover, what is changed and who is involved can vary widely. Therefore, any model of change will necessarily be big picture and generic.

- Change journeys have phases, not steps. Almost all change journeys do not follow orderly steps but are messy, complex processes in which only general phases can be recognized. Yet even these phases can overlap, and looping back can take place.

- Change journeys have five phases. Each organizational change will pass through five phases: Formulation (determining the change strategy); preparation (getting ready to change); mobilization (initiating the change); realization (implementing the various changes); and consolidation (wrapping up and securing the changes).

- Change journeys are hazardous, not straightforward. Change is not only messy but also full of ups and downs, due to the difficulties that must be dealt with along the way.

- Change journeys have five hazards. Each phase has its own key danger that needs to be handled: The ambiguity hazard is the threat of a vaguely formulated change direction; the contracting hazard is taking on a change for which the organization is not ready; the momentum hazard is not reaching take-off speed; the setback hazard of giving up after a disappointment; and the anchoring hazard is not securing the almost completed change.